“A BOAT RIDE OVER THE NIAGARA”

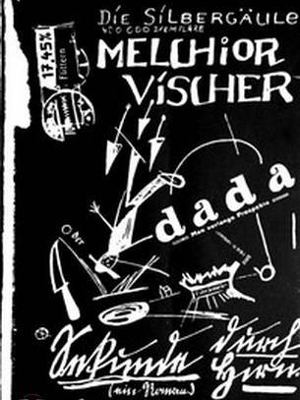

Second through Brain appeared in 1920 at the Steegemann publishing house, in the dada series called “Die Silbergäule” (“The Silverhorse,” also obliquely invoked in the text), with a cover design by Kurt Schwitters. Apart from using some of the typical Dadaist stylistic techniques as visual typography, non-lexical onomatopoeia, meta-narration, and textual montage, Second through Brain also seeks to programmatically align itself with the Zürich/Berlin dada group. There is, famously, the “intertelluric greeting to Serner and Tzara,” with the prospect of “a boat ride over the Niagara” (74)[1] – emblematic of the movement’s zany shock tactics and almost self-sacrificial measures to which it resorted. These are brought into relief in this crucial passage:

Do you think me crazy? Oh no! it’s only my environment that’s moronic, civilised, besmeared, hence me the oddball. Especially odd the superpious healthy fat folks & gym teachers. We want to smash culture into pieces, also the bourgeois madness, which is so often nicely lacquered and bound in Morocco leather, we’re heading out all the way to the utmost end, bordering on the big freedom: ur-being. We rubble, we rubble, & if da da, from the ground up, at first cringed lacquered speech, then the only thing remaining now would be the whole big DADA. – Here’s to you, Huelsenbeck, Baader & Schwitters. We have no pity. We show saneness & whoa common sense from its downside. (97)

In this programmatic statement, Vischer’s disparagement and critique of the perceived “bourgeois madness” and the “lacquered language” of his contemporaries fits the bill (almost to a fault) of all the four major phases in the social roles assumed by the avant-garde, identified by Renato Poggioli in his seminal The Theory of the Avant-Garde. The first of these, activism, refers to the avant-garde taste for action and agitation for the sake of agitation, and the pleasure derived (“We have no pity”). From this activism directed at anyone and no-one (“the superpious healthy fat folks” as well as “gym teachers”) follows a more general social attitude of the avant-garde termed antagonism. Nihilism is the third, destructive phase manifest in the work of the Dadaist (“we rubble, we rubble”), issuing into agonism,[2] the pathos and suffering of the artist/victim/hero – chiming well with Vischer’s desire “to smash culture into pieces, also the bourgeois madness.” A case in point, then, of dada ideology if not technique? Indeed, it is the textbook, clichéd character of proclamations such as this that challenge the extent to which Second through Brain is dada in actual writing rather than programmatic agenda. Literary historian and editor of the Vischer correspondence Raoul Schrott raises some valid objections to Vischer’s Dadaist credentials: his writing, after all, does preserve the “correspondence between speech- and reality-structure,” which dada sensu stricto sought to do away with in the first place. The “various paradigms” juxtaposed by Vischer in order to “cope with the panta rhei” still keep him, to Schrott’s mind “within the logic imposed by these semantic fields.”[3]

The Paris/Zürich/Berlin dada axis, for the Vischer of 1920, evidently presented a more international—and thus more apposite and advantageous—artistic worldview than the Prague offshoot of German expressionism. Vischer’s expectations from his dada alignment were nothing short of earth-shattering: in a French salutation to Tzara and Picabia from April 1920, Vischer announces the publication of Sekunde as no less than “a bomb which has to burst open with infection the skulls of our dear ‘bourgeoisie,’” and promises to set the world on fire with it. The wish/reality discrepancy is close to poignant. While assuring both that “Second is the first Dada-novel and must march triumphantly […] across Europe,” Vischer still has the need to beg for their interest: “I beg of you to kindly take interest in my novel […] and please send me three copies each of every critique.”[4]

As his rather one-sided correspondence with Tzara suggests, Vischer’s avant-garde affiliations, just as by now almost everything else about his “life of another,” were tenuous at best. Jäger points to some quite pragmatic reasons why Vischer would’ve found it rather strategic in the Prague of 1920 to align himself with dada, a marriage for reasons other than of love:

For Vischer, dada presents a chance to overcome the late-pubescent and socio-cultural crisis and to forge a new identity by foregoing the one he’s been allocated. At the same time, it becomes clear that the “freakily high-torqued novel” is just a means to discharge oneself and to soar up, for when looking at the much larger publication of Teamaster in 1922, it’s evident Vischer’s abandoned Dadaism already.[5]

Vischer’s change from F to V, from an “Expressionist” in 1918 to a Dadaist in 1920 to a dropout in 1923 (and whatever followed afterward) should be seen in the context of the political changes in the Central Europe of that period. Born into, for all intents and purposes, a German-speaking country, after the 1918 establishment of Czechoslovakia, Vischer found himself a member of an ostracised (and in reaction radicalised), dwindling language-minority. It certainly wasn’t Vischer’s decision to fight in the war—even less so, on the losing side—nor was it his choice to end up as war casualty in Prague, a city in which he felt increasingly alienated and isolated. And it seems there are grudges held in Second, for no other city (not even Vienna) gets quite as harsh a treatment as this “yellowed funnel by the plagued canopy bed Europe”:

The city of howler monkeys & fleas, of corruption, of the New-European bacillus idioticus militaris, also the crucial point of all the pennons of an occidental world with arsphenamine treatment, head office of pushers, who hustled bull market with state insolvency, of clogged sewerage, of the fastest streetcar in the world & the city of six thousand ministers. Everybody is, has been or shall be, a minister. In exchange for that the nation’s splendidly off. (82)

Given that Vischer had no Czech, his envisaged plan of a Prague dada-branch may not have been as plainly opportunist. In the cultural and linguistic policy of the new Czechoslovak state, Vischer and scores of his Prague-German compatriots were becoming increasingly marginalised. By 1923, with Second through Brain failing to “march triumphantly across Europe,” it was the author who, quite logically, had to undertake the marching. Less logical is Vischer’s conviction that the path of any and all avant-gardists should’ve been or was to be paved with golden nuggets.

Three decades later, having hit rock bottom with the humiliating republication of the Hus biography, Vischer embarked on his last project of writing confessional, quasi-mystical lyrical poetry not intended for publication. In the poetry—most of it religious hogwash[6]—Vischer occasionally fondly reminisces over life in Prague and romanticises its monumental past. Yet the St. Vitus, the Castle, the Golden Lane, all serve as backdrop for social criticism no less scathing than that of the Second period: “They all, women and men, they all / inside kneel together in intimacy and outside walk up against each other in hostility.”[7] A criticism also directed at Vischer’s younger avant-garde self: “Contrition and frankincense no longer burden me / as I stand here, petty, impudent and self-righteous.”[8] Evidently, V/Fischer’s catholic background that had stood behind so much in his life, in the final retrospect, separated him from both his avant-garde aspirations as well as homeland: Hradčany is apostrophised as “the heretic ark over the city, / shining in twilight.”[9]

“A SHROVETIDE PLAY”

The when and how of Emil Fischer’s metamorphosis into Melchior Vischer having been established, the question still remains: why? Jäger offers as good and educated a guess as any, suggesting it served a double purpose, assuaging his Catholic upbringing in the face of what were admittedly unorthodox artistic aspirations, while also acting as the vehicle for their embodiment. “Melchior” quite plausibly refers to one of the so-called three magi—whose feast (the epiphany) falls onto 6 January, a near overlap with Fischer’s own birthday—and “Vischer” seems related to the brass-founder and church sculptor Peter Vischer (the Elder), who died on 7 January 1529. Jäger:

Since Fischer stemmed from a catholic family, it’s not unlikely that he found his pseudonym while reading a clerical/middleclass almanac, in which he combined the two entries found under the dates of 6 and 7 January. Accordingly, the chosen name refers to kingship, Catholicism and artistic calling.[10]

Vischer’s penchant for the charms of “kingship” would of course, later on, rear its ugly head in his fascination with the seductions of Nazism, but the Christian resonance of his artistic pseudonym is of more direct interest for a debut text like Second through Brain with its concluding reference to “censers” and a prominent typographic image of the cross.

Second through Brain presents a special kind of iconoclastic text in refusing to undermine the dogma and expose the ridiculousness of organised religion, but reduces its critique to drawing upon Catholicism’s own tradition of misrule and the carnivalesque. The text’s programmatic “Pro- and Epilogue,” classifies Second through Brain generically as a “Shrovetide play” (Fastnachtspiel, 51), placing it in the tradition of excessive merry-making prior to the forty-day period of Lent fasting (Fastnacht literally refers to the eve of the fast). Equally significant for the Catholic dimension of Vischer’s text is that regulating the Shrovetide unruliness was the institution of confession: before embarking on the merrymaking, all ye faithful were expected to be “shrived,” i.e. absolved from their confessed sins. The ensuing carnival would, over the course of centuries, blend theatrical and sporting events, performances of masques vying for the good believers’ attention with games of football. The episode in the cloister at the St Gotthard is emblematic of Vischer’s mockery of Catholicism: the brothers with “their barrelbellies” kneel down at the sight of “an abbot from Rome come here to inspect the kitchen” (they’ve only his word for that) and pledge to “henceforth chastise themselves with chestnuts” (63). There’s only drinking and c/arousing at the cloister, with the kitchen maids “all worse for wear” because of “the good brothers,” whose cry of piety is, “haha, dada, hallelujah” (63).

Apart from participating in the “Shrovetide” tradition of festive misrule, Second through Brain is also steeped in Catholic tradition by “making it new” largely through parodying the old, which the modern cannot plausibly do without. On one of his journeys, Vischer’s protagonist is caught “thinking of Thomas Aquinas, then of Grünewald, at last of Gauguin” (86), arriving at modernity only via mediaeval scholasticism and gothic expressionism. There’s, in other words, despite Vischer’s dada innovation, a sense of traditionalism, of conservatism, much of Second through Brain feeling, underneath its tawdry cloth flowers and flashy ribbons, like an old hat. A point brought home towards the end, the only identification mark of the protagonist’s corpse being his “oddly pushed-in shuteyes, as in ancient Egyptian mummies” (100).

A “FREAKILY HIGH-TORQUED” SECOND THROUGH BRAIN

What the Shrovetide did to the medieval conception of time (stopping it dead for a whole week), space (collapsing its everyday boundaries) and social identity (reversed and deranged, the holy profaned and the profane hailed), Vischer’s Second through Brain does to narrative realism. It freezes its temporal duration, collapses its spatial boundaries, and lampoons its habitual underpinnings.

Vischer’s narrative consists of a series of disconnected vignettes, flashing through the mind of one Jörg Schuh, a stuccoist in the process of falling off the scaffolding of a forty-storey construction site (N.B. the numeric parallel with the forty days of Lent fasting). Staring certain death in the eye, the protagonist embarks on a cab ride “on the great Milky Way” which takes him through his past life, both actual and also the many might-have-beens. Although the setting of Jörg’s fall has no place name proper, most of the flashbacks do have a local habitation: his conception at a Central-European brothel and his birth aboard an Andalusian barge in the Lisbon harbour give rise to a highly erratic, if also very place-specific travelogue. Throughout, Jörg appears in different times, spaces and impersonations: he witnesses his own conception through a union between a negro pagan and central-European prostitute, he experiences his prenatal life, his birth, his existence as a newborn, and an interminable series of further careers/incarnations: an athlete, excavator-driver, carver, fake monk, stonemason, grammar-school pupil, footballer, Eskimo, a “president of America,” a coolie in Japan, a lecturer on political economy in an African “Caoutchoucstate,” a rat in Beijing, a “man in the moon,” a Jew-killing minorite priest, president of Germany, then back to the falling Jörg Schuh and, finally, a “brain radiantly splattered” (100) against the pavement. This fantastic roller-coaster ride through the head, in turn, takes Jörg from Genoa, St. Gotthard, and Vienna, to “a thermal city in which Goethe had stayed temporarily” (i.e. Vischer’s native Teplice) and onwards: to Lapland, Nagasaki, Notre Dame, “Caoutchoucstate, Africa,” Shandong, the Moon, Prague, Madrid, Fiume, Budapest, Berlin, Brazil, Cape Horn, Chicago, and via London back to “the antiquated appetitebiscuit Europe” (94) and toward the great beyond.

These vignettes, as the text’s subtitle has it, are “freakily high-torqued” before Jörg’s/the reader’s eyes, until reach the ground he finally does, landing “on the plaster of smashed heads & necks” (99). His corpse gets collected for inspection at the clinic and ends up blessed, just as the text itself, with a final cross, to the accompaniment of “swinging censers” (100). Narrative time, although frozen and referred to only obliquely, can be determined from only two elucidating allusions to contemporary political-social matters. Vischer’s Prologue only mentions the manuscript having been “written in Prague at a time so molluscan I cannot really determine it mathematically” (51) and almost all of Jörg’s shenanigans take place in perfect timeless simultaneity where Pythagoras coexists with Hedwig Courths-Mahler, a turn-of-the-century proto-feminist writer. But two pieces of trivia do place the text within the context of 1920: the mention of “Mr Ebert and Mr Noske” (president and war minister of the Weimar Republic) having “their pictures taken in sumptuous swimmingtrunx” (94) refers to the late-1919 public hullabaloo caused by the publication of these two prominent figures’ photos in swimming trunks. Even more topical is the reference to “Clemenceau in Egypt” (65) – the French ex-prime minister did take a vacation in Egypt from February to April 1920 (for more, see the “Notes” section).

JÖRG SCHUH’S DADASEIN

A consistent (and unfortunately untranslatable) pun throughout Vischer’s text lies in the homophony between dada and “da, da” (“there, there” in German). And yet, in the episodic, disjointed, and radically plural narrative of Second through Brain, the protagonist is never quite “there,” his identity, just as his whereabouts, always likely to undergo a complete change, paragraph by paragraph.

So breakneck is the speed of these changes that Jörg himself has difficulty keeping up, as when he “wondered about the sudden spatula in hand, which traversed untoward crannies through the wood” and only later “remembered that yesterday, having been picked up on the street […] he’d promised to learn god-carving” (62). Again, it’s not so much the what as the how that’s new: Vischer’s narrative is 20th-century energised, and supersized version of the long German picaresque tradition on fast-forward, extending all the way back to Grimmelshausen’s Simplicius Simplicissimus or the folkloric Till Eulenspiegel cycle. Also, Jörg’s opening encounter with the “Milky Way cabman” in “a specular tophat” alludes to Faust’s meeting with Mephistopheles, especially since Jörg’s first desired destination is the brothel (54). Similarly to these literary precursors, Vischer’s Jörg Schuh is a “one-dimensional” man, whose raison d’être is the fulfilment of the basic physical needs: hunger after food, need for pleasure, and desire of power and fame.

This projects into the conjoined themes of the text’s gender- and race-politics. Jörg Schuh’s “dadasein,” so to speak, subscribes to some deep-rooted conventions and stereotypes, however, not without some effort on Vischer’s part to undermine them. It’s true Vischer does go along with them for quite a while: throughout, women appear as sexual objects to be used and discarded by the ever-horny protagonist. Although the protagonist’s fatal fall is caused by his eyeing “the huge bosom of maid Hanne from the skyscraper opposite no. 69” (53), this does not seem to deter him from giving free rein to what could be diagnosed as full-blown Don Juanism. From the first encounter with a woman called Rahel, Jörg’s one and only “talent & strength” (60) is his lust after, and capability of, superhumanly satisfying legions and legions of women, which reduces whatever possible character motivation and psychology he might possess to that of an itinerant male member. For instance, he repays his first employer, measurer Sebaldus, by impregnating his wife; all Jörg manages at a St Gotthard cloister is to “burst open within one night” the only virgin among the kitchen maids “so she forgot herself in blood” (63); on his journey to the North Pole he has “a hundred Eskimo females standing outside, begging for his manhood,” whom he “conquers” by night and has them “kiss his feet” by day (72).

The only woman with some backstory, and the only one Jörg deigns to marry, is “Miss DDr. Bathseba Schur” (“Shearer”), whose “braininess”—two doctorates in medicine and philosophy at the tender age of 24—apparently renders her unwomanly, a specimen of “exceptional manwomanhood” (69). For Vischer, the dada revolution was evidently not fought for female emancipation, nor, for that matter, was the “Jewish question” among its interests: when Bathseba dares to “circumcise her new, oh so mighty husband” (71), Jörg gives her a mighty slap and takes to flight. The same goes for racial stereotyping. The translation replicates the original’s “negro” as a race-marker, for in 1920, it was a far less scandalous and improper appellation than it’s become to our politically correct eyes and ears today. Again, Vischer has all the racial stereotypes in place and at work: in the opening scene, the negro “dances, [… hearing] the jungle roar,” then “grins, baring his teeth,” his “twitching sex” having impregnated a white harlot (56). During Jörg’s visit to “Caoutchoucstate, Africa,” the locals are habitually referred to as “cannibals” (79) and in one episode they want “to tear the skin off the smug ivory man” (80).

At the same time, it’s to these “cannibals” that Jörg delivers lectures on subjects such as the theory of relativity and “general suffrage for women” and is described as speaking “Cannibal better than European.” The Negroes, although lacking mod cons like the telephone, still understand Morse code and even establish a “Club of female negroartists” (79). And, the opening scene of Jörg’s imaginary birth brings home the highly provocative point (at least for 1920) of Jörg’s racially mixed origin – he is born with “motley ears: the one white, the other black” (57).[11] The voice in Jörg’s embryonic head even has it that “the white [ear] is dumb like field Europe, hears nothing. The black one, however, hears everything: the bygone & to-be, till they’ve both come full circle” (55). As if the black race were endowed with wisdom and powers of divination to which the white race has grown deaf. Upon conquering his first Eskimo, Jörg gives vent to the following proclamation:

Here still reigns the free, primitive huge lust of procreation. Da da! Here’s the mother of all culture. Where I come from, the accursed west, there’s just the grin of indictable exhibition instead of culture. (72)

These and other excursions into non-European cultures and Europe’s colonised other serve Vischer the obvious purpose of critiquing some of the underpinnings of European socio-political ideology. And, after all the chauvinist humiliation and reduction to which Second through Brain subjects women, comes the following passage from Jörg’s presidential inauguration speech:

In the end there’s no difference whatsoever between penis & vagina, the more so when they’re sweetly sighingly together, both consist of flesh, although of a slightly diverse geometrical form, they smell of mystery, which just consists in friction with the ignition of knallgas. (89)

Not only is the penis no different from the vagina, but ultimately, one feels that it is the male psyche’s fear of, and incompetence in front of, its female other, that is caricatured and mocked through Jörg’s obsessive single-mindedness, the joke ultimately on him.

And on others, as well. Most unambiguous is Vischer’s critique of that which he sets out to abandon and keeps coming back to: “the plagued canopy bed Europe” and its insane power-hunger that recently (and Vischer knew this first-hand) brought the world to the brink of self-destruction. Politicians of all ranks, real or imaginary, are a constant target of satire and scorn – as the great machinists of the sort of wisdom that drowned millions in the trenches at Verdun and gassed hundreds of thousands at Ypres. This is, of course, the dark and serious undertone of most of dada programmatic inanity and irrationality – in a world whose rationality has killed millions, zany is the new wise. This undertone also runs the length of Vischer’s text from the Prologue’s opening nod to Carl Einstein’s point regarding “the courage to say utter rubbish” (51). An emblem of Vischer’s mockery of European rationalism is the wonderful scene with Pythagoras as the Man in the Moon, insisting on the falseness of his theorem, for “all is circle, never square,” square defined as “endless nonsense with negative power” (81). If this isn’t ludicrous enough, Pythagoras’s tidings get distorted and vulgarised into an advertising slogan at the Berlin parliament when Jörg passes on “his friendly greetings, telegrams and the offer to buy his suspenders, which he manufactures himself, brand ‘Hercules’” (90). And when Jörg does finally relate the revision of Pythagoras’s theorem as “there’s no straight line whatsoever, there’s only circle,” the reception is quite unambiguous, “they laugh, they all laugh, laugh” (95). The last poignant laugh, again, is on Jörg, for his fall is no circle but a fairly straight line with some quite definitive end.

SECOND THROUGH BRAIN “RADIANTLY SPLATTERED”

The world of 1920, Vischer’s Second through Brain seems to insist, has turned religion into profanity, politics into opportunism, humanism into ridiculousness, and learnedness into stupidity, and its only straight line is the trajectory of life falling into death. But Vischer’s text, while posing as fictional dada manifesto critiquing (and lampooning) contemporary socio-politics, also presents a theory-in-practice of art. Most obviously, Vischer’s protagonist is an artist in his own right, even though his is a practical art – stuccoing, halfway between masonry and painting/sculpting. On his downward trajectory, he does dabble in various trades and practical arts (bricklaying, carving, engraving, etc.), before finally reverting to his original calling of a stuccoist, his self-consciousness having undergone something of a sea-change in between:

I’m an artist!… I’ve learnt something, I can something, I am something, even when imaginarily.

For suddenly he was a stuccoist. But then again he’d once been told he’s more than that, he’s an artist. (95)

The question of what constitutes art and what makes those engaged in the activity into artists, is of course crucial for the WWI generation of avant-gardists, and for dada in particular. Curiously, apart from a Nietzsche quote, Vischer chose for the motto of his text a self-quotation from a passage of Jörg’s transformation back into the falling stuccoist: “Art is, if not already a prejudice, then still always a private view,” such is the “dubious thought” (96) flashing through Jörg’s brain as it is about to bespatter the pavement. This insistence on the private, anti-public or communal aspect of art chimes well with what later theorists of the avant-garde like Peter Bürger came to regard as a defining trait of Dadaism:

Dada, the most radical movement within the European avant-garde no longer criticises the individual aesthetic fashions and schools that preceded it, but criticises art as an institution: in other words with the historical avant-garde art enters the stage of “self-criticism.”[12]

Apart from self-quotation and self-parody, there is also self-representation, as Vischer himself is mentioned in Second through Brain, and argument is put forth (just as Jörg is sworn in as president) that Dadaism and Dadaists be exempt from paying taxes, “for surely Melchior Vischer’s dada-games are the most inexpensive we’ve got at the moment” (90). The darker point of this satirical barb concerns the permissibility, the acceptance of Dadaism by powers-that-be: what is the point of launching an aesthetic revolution if it fails to affect the political status quo?

There’re three further critical points Vischer’s text seems to be making vis-à-vis the 1920 situation of fiction and art. The first one’s to do with its academic underpinnings, subjected to systematic buffoonery, as when, at a restaurant, Jörg is served “good Pomeranian geese,” all of which have “a PhD in German studies, write lyrical poetry, diaries, drama too” (88). That the alternative value-determining force, the literary market, has very little charm for Vischer, is brought home by his satirising of such popular literati of his times as “HCM” and “otto-ernst” (see Notes), who happens to be present at the pub table, “wondrously naked, only behind him a gorgeous bunch of flowers stuck in his honoured buttocks” (88).

The second point concerns the “art” of advertising. Vischer the newspaperman populates his text with a plethora of commercial slogans and catchphrases, knowing full well that the newspaper is the medium concentrating the most innovative potential within the print culture of his time. The very segmentation of his book into brief, usually single-paragraph instalments, and the non-linear, episodic and fragmented story told through them, both clearly point to a journalistic sensibility at work. Ironically, Vischer’s only typographical experimentation, apart from the occasional non-lexical onomatopoeia, springs from his inclusion of advertisements into the text – it is, after all, “a noticeboard aglow with golden letters” advertising “eggs and buttershop” (98), that is the last thing flashing through Jörg’s brain. A critique bringing into relief the banalisation, through the brevity and flashiness of the advert, of public discourse, resounds most prominently in the Pythagoras episode, where the refutation of his theorem is presented through nonsensical commercial jingles (“Odol cleans the teeth, indeed” [95]) and Pythagoras’ defence is undertaken via an “advertisement banner”:

Do not laugh, Your Lordships, for you don’t know if it’s yourselves you’re laughing at. But then it’s I who laugh. Who can tell you a square always and everywhere remains a square. Laugh you all, laugh! (95)

Apart from the newspaper, the speed and disconnect of Vischer’s “freakily high-torqued” narrative also strongly resounds with its third art-related topic, the cinema; its ride in a Milky-Way cab reminiscent of the 24-frame-per-second pace of the moving pictures, and, together with it, symptomatic of the acceleration of all things off-screen to which film contributes. “Off to a brothel, then!,” commands Jörg, and on the next line, one is already there, with an impersonal voiceover beckoning:

Come Jörg, watch how you’re being made, it stank drunken, how black and white reeled in the small divanadorned chamber, and the woman sighing rubbed herself against the musclehard loins of the Moorish athlete, what an enigma wheezing off. (55)

The copulation between the negro and the prostitute is described with abstract visual economy of “black and white reel[ing].” There is the audio “sighing” and “wheezing,” even some olfaction (“it stank drunken”), but the primary sense, as ever so often, is the sight of the voyeuristic proclivity (“come watch”). Again, cinema is elevated and imaginatively reconceived (e.g. “Suddenly a crank somewhere in my braincinema gyrated” [95]), but also satirised as a trivialising, lowly art form; as when Jörg celebrates New Year’s Eve by “a Henny Porten screen” (68), or when the narrator satisfies the need to provide a second, more final ending to the tale, “for the sentimental, everything-ought-to-have-an-end folks with tearjerked, possessed cinesouls out there” (100).

In a culture dominated by the frag/seg/mented typography of the newspaper and the visual mode of the cinema, where the fiction’s been partitioned between academics and the marketplace catering to the reading masses, the question to be posed is, how is literature to continue playing a role of any importance? Vischer’s answer in Second through Brain is, only by taking stock of contemporary advances in other media and art forms, in accelerating its stories to the breakneck pace of the times. The first necessary step toward doing so is, of course, to adjust its language.

“HEAR THE WORD”

Of course, Second through Brain is much less an interesting story or a dada manifesto/programme than it is a linguistic experiment, an attempt at making language, together with the narrative, to “torque freakily high.” It is a text that forges its own peculiar idiom, lexically and morphologically, as well as grammatically and syntactically. All these levels can be seen at work in the following, more than less randomly chosen passage:

Giddy at the odour of his sweat, nearly snorted her head off, panted, drank, bit. By day she held him hidden in a small room. No longer savouring her body, her cravings, he sprang up, whacked jingling through the window, fell sorely onto the cross, already up, over the park masonry in a swing, ran upcountry. Fruits wrenched from trees, nourishment to him. Through dust, which whitely poured through all the winds, past cloisters, avoiding sbirri, who were, capped in scarlet red, searching the army streets looking for him, finally at sunsink he entered the noisy broadthroughstreeted city. He threw into a hawker’s oafish face question after the name of the place: Milano. (62)

The dramatic, rhythmical, concentrated language-effect comes about by Vischer’s utilisation of the four principal means: syntactically short units focussed on verbal phrases (“no longer savouring… he sprang…whacked jingling… fell… ran”); elisions of grammatical words like prepositions (there’re no “ands” to mark the last members of series) or auxiliaries (“got already up”; “fruits wrenched from trees were nourishment to him”); and morphological and lexical neologisms based on portmanteau agglutination (“sunsink”; “broadthroughstreeted”). This proclivity for portmanteau compression affects not only Vischer’s nouns or adjectives, but also adverbs – reading on within the same paragraph, Jörg sleeps “morningtill” and later on treads “Alpsward.” This goes hand in hand with Vischer’s emblematic – since already entailed in the book’s title – tendency to omit articles, both definite and indefinite (not “Eine Sekunde durch das Hirn,” and consequently not “A Second through the Brain”).

All this, to which add Vischer’s predilection in archaisms, slang, phonetic misspellings, and various jargons (dealt with in detail in the Notes section), gives the passage (and the entire text) an air of intensity and economy, if also unsettling evasiveness. Some of Vischer’s portmanteaux are flashy, if rather forced, puns, of which some are translatable straightforwardly (as when “hyena” and “hygiene” combine in order to form “hyegienic” [93]), some less so (“bedauert” / “betrauert” approximated as “bemourned” / “bemoaned” [63]). Some are rather innocent-looking, and untranslatable, as in the remark regarding Jörg’s black ear, “es hört so genau, daß es weiß” – with the delightful double entendre on “knowing” and “whiteness.” Our translation can only approximate this by the more forced “it hears so exactly it’s sharp-whited” (55).

Regarding Vischer’s experimentation with/against articles and noun-determination, a brief note on the translation here will be necessary since there’re differences between the morphological makeups of German and English that allow the economy of his style to get across only to some extent. In the above passage, for instance, the original’s “landeinwärts lief” is faithfully reproduced as “ran upcountry” and “warf er […] Frage,” as “he threw […] question” – i.e. without the “correct” article.

However, German adjectival declination allows adjectives to stand-in for articles as case-determiners (e.g. Vischer has “in kleinem Zimmer” instead of the more usual “in einem kleinen Zimmer”), which has no analogue in English, and having “in small room” would not only sound faulty, but also take Vischer’s experiment a step further than he himself ventured, producing a translation of a defamiliarisation more alien than the original’s. The translators have tried to make up for this “wordiness” by making as much use as possible of abbreviated forms of auxiliaries and of ampersand in lieu of the usual coordinative conjunction – at least approximating the sense of deviation from the norm of the “literary” English of 1920 produced by Vischer’s compression of gender and declination markers in his German.

“A PRETTY FALL, A FI – – – ”

At the time of the completion of this translation, we are nearing the centenary of the founding of the Zürich Cabaret Voltaire and, together with it, dada as such. One ought to raise the question of how useful, after almost a hundred years have elapsed, a translation can be in the case of a book so much of its own day and age, by an author that the past century seems to have done perfectly well without, in fact would rather keep in near-complete oblivion. In 2015, as in 1920, time again seems to be “molluscan,” but to bemoan that “inanity” passes off for “apodictic wisdom,” that to be “daft” is so often to be considered “clever,” is to commit a banal cliché; boundaries between the “made-up” and the “true”—if they ever were there—have in any case long ceased to exist. Only what used to be avant-garde shock tactics and reserved for special occasions is now called TV News Show and happens on a daily, hourly, minutely, secondly basis. But for a time again so similar, Second through Brain’s journey across this planet and off to the Moon and the Milky Way, as well as Vischer’s own journey from F to V and back again, from dada to Nazi to West/East Berlin and to the great beyond, perhaps offer a few potentially useful reminders.

The text reminds us that only such aesthetic programme is revolutionary that seeks (to paraphrase Marx) not only to describe its own present condition and medium, but to change them. That mere parody and caricature—with economic gains in mind moreover—can never bring about a change in and of themselves. That fiction, if it is to keep pace with the general acceleration of civilisation, has a lot of catching up to do. That fiction immersed in opportunism and commercialism need not be opportunist and commercial itself. The author reminds us that radical artistic tendencies do not easily translate into radical socio-political positions; that they can actually flip into their opposite when geared up to organised political praxis; that “molluscan” times breed “molluscan” characters. In 1918, not only did Fischer the pacifist soldier change into Vischer the radical poet, but Fischer the Sudeten-German was turned into the citizen of the artificial pan-Slavonic anti-German league called Czechoslovakia. His slightly opportunist and rather one-sided attempt at aligning himself with international avant-garde can be seen as a logical step toward overcoming his WWI traumas by creating an international network (stretching out from Prague via Berlin, Hannover and Zürich to Paris) of creative brains within which to weather whichever future storm may be in store. How this project was to be frittered away, and why V/Fischer the Sudeten-German was to founder together with it, would be a subject for another introduction to another book – any attempt to read the Emil Fischer of 1940 back into the Melchior Vischer of 1920 should be avoided.

Whether or not these reminders are in any practical way useful today, or can only be revisited as atavisms, as fossils from an age so ancient it is incomprehensible to us (just as the Christian crosses the text evokes throughout), it is this project’s firm belief that Vischer’s Second through Brain deserves at least a chance at a Second Coming, since the second it portrays speaks not only of its own time, but also anticipates much of the following century and our own time, and the brain it passes through—even a hundred years after it “spritzed on the asphalt, broke forth into yolk, mixed-in slimily with the muck & expired” (98)—is still well worth an attempt at resuscitating.

—

[1] All translated quotations from Sekunde durch Hirn are taken from the present edition.

[2] Renato Poggioli, The Theory of the Avant-Garde, trans. Gerald Fitzgerald (Camridge MA & London: Harvard University Press, 1968) 22-30; 61-2.

[3] Vischer, Unveröffentlichte Briefe, 35.

[4] Vischer, Unveröffentlichte Briefe, 7.

[5] Jäger, Minoritäre Literatur, 463.

[6] Couplets such as “I felt, I imagined: / the Now is eternity” or “A little wind, then a timid rain: I hear God whispering to me” run the length of Serke’s selection (Böhmische Dörfer, 181-2).

[7] “Qtd. in Serke, Böhmische Dörfer, 181.

[8] Qtd. in Serke, Böhmische Dörfer, 181.

[9] Qtd. in Serke, Böhmische Dörfer, 180.

[10] Jäger, Minoritäre Literatur, 459.

[11] This, as my co-translator Tim König reminds me, is quite plausibly yet another one of Vischer’s many parodies – here, of Wolfram von Eschenbach’s Parzival epic. Parzival’s half-brother Feirefiz, son of Gahmuret (also Parzival’s father) and the Moorish queen Belacane, is born with a skin made up of black and white patches.

[12] Peter Bürger, Theory of the Avant-Garde trans. Michael Shaw, with foreword Jochen Schulte-Sasse (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1984) 22.

Published by Equus Press.

published: 3. 4. 2016