Originally published in Subtexts: Essays on Fiction (Prague: Litteraria Pragensia, 2015) 51-63.

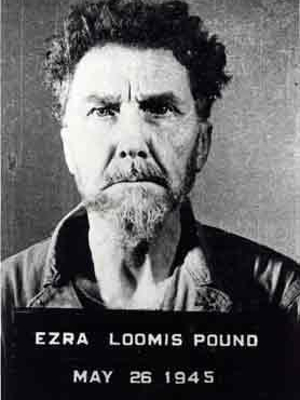

As Pound noted in his portrait of the artist as an ironic man, the demand of the twelve years that had come to constitute his London “age” was first and foremost that of the “image.” Hugh Selwyn Mauberley surveys his 1908-1920 London period, employing his Imagist/Vorticist techniques, yet is marked by a sense that, like the era, so the techniques are exhausted, over, ready to be metamorphosed. Parallels with Joyce’s 1904-1915 Triestine exile abound: both were periods of aesthetic programmes, of initially modest successes met with immodest critical hostility, of frustrating journeys back home which only underscored the growing sense of alienation. Both Pound and Joyce had arrived in their cities of exile at the age of twenty-two, both with the aspiration of becoming poets (which Joyce, of course, was wise enough to abandon soon and Pound wise enough to stick to), and neither left until they made their breakthrough – Joyce having published, at long last, Dubliners and embarked upon the serialisation of A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man (on Pound’s insistence, in Harriet Shaw Weaver’s The Egoist), Pound having passed through his Imagist and Vorticist periods and already commenced his lifelong Cantos project. Both of their exilic sojourns drew quickly to their closes (Joyce was left jobless and deserted after all of his pupils were conscripted during the First World War, while Pound found himself bemoaning the “botched civilisation” of London during the Post-World War I period and soon left), and finished with a tone of disgust in their writing: Joyce through Stephen Dedalus and Pound through Mauberley, both exorcising their Aesthetic propensities and ironising their fictional past selves. Although they were both to explicitly draw lines under their pasts, and both would exchange their first exiles for Paris (Pound directly from London, Joyce via Zurich), it is undeniable that both Trieste and London were to leave indelible traces on their lives and writing. During his penultimate brief sojourn back to his dear dirty Dublin in 1909, Joyce writes to his partner Nora: “Why is it I am destined to look so many times in my life with eyes of longing on Trieste?”[1] and as late as a 1932 he includes a passage in “Work in Progress” that has his “altered ego” Shem recall his Triestine descent into alcoholism with peculiar nostalgia: “And trieste, ah trieste ate I my liver!”[2] Pound is even less ambiguous; again in 1909 he writes to his college friend William Carlos Williams: “London, deah old Lundon, is the place for poesy.”[3] And as late as The Pisan Cantos, written almost three decades, in 1945, after the fact, Pound recalls, apart from the many other London experiences, his first lodgings near the British Museum, across an alley from the Yorkshire Grey pub and the “old Kait’ […] stewing with rage / concerning the landlady’s doings / with a lodger unnamed / az waz near Gt Titchfield St. next door to the pub / ‘married wumman, you couldn’t fool her.’”[4]

The point of these parallels is to underscore their haphazardness. One might rewrite the paragraph above replacing every Pound/Joyce analogy with an equally valid instance of difference between the two. These parallels are willed links imposing a pattern of order upon the chaos, vicissitude and randomness that is human life. Still, however subjective and arbitrary, such links produce poetic energy, and bestow a meaning, if not sense; meaning as such arises only out of such links and patterns, and outside the wilful impositions and biases of human sense-making lies the unthinkable, un(re)presentable.

Such is, at least, the strong belief of the master parallelist and the subject proper of this brief comparative piece, Iain Sinclair. Such is, also, the underlying belief of this essay – that there is a line of energy streaming from Pound to Sinclair, a fundamental affinity between their poetical projects. Between the “pedagogical” genealogy of Pound’s Cantos composed of a multilingual, broadly intertextual corpus of texts aiming to encompass the history of socio-cultural development of both the East and the West, and Sinclair’s “psychogeography” as recorded in both his poetry and prose, which consists in reading urban space and architecture as palimpsests of their various pasts and presents, in archiving their past development—both historical and fictional—and in recording, re-presenting their present effects upon the recipient psyche of the observer. The affinity lies in Sinclair’s insistence on radical metaphor, on direct juxtaposition of disparate ideas and images. A closer reading of a passage from his Suicide Bridge will reveal a debt readily acknowledged to Pound as the source of these techniques.

Biographical parallels between Sinclair and Pound abound, but touches upon just two will serve here. Sinclair, too, chose London for a self-willed exile, as the ultimate and permanent stage of his development from his early childhood in Cardiff via college years at the Dublin Trinity. His choice of London comes from within a consciously assumed literary paradigm; here is Sinclair reminiscing, in 2003, about his college years in Dublin:

Dylan Thomas was the model, in a sense – not knowing exactly how the story went, but knowing that he’d got away to London, and that was what you had to do. […] My twin passions, really, were poetry and cinema. Dylan Thomas was the initial model, but I soon moved on to Eliot, Pound, Hitchcock, Buñuel, Orson Welles.[5]

Secondly, before becoming a literary persona, establishing himself as one of the most important contemporary writers in and on London, or, as critics have put it, “our major poetic celebrant of the city’s hidden experience, its myths and subcultures,”[6] Sinclair engaged in the modernist practice of self-publication, founding his Albion Village Press to publish his Lud Heat (1975) and Suicide Bridge (1979), collage texts of essay, fiction, and poetry; the texts, for obvious reason, under focus here.

Already in his 1975 poem Lud Heat, subtitled A Book of the Dead Hamlets, Sinclair launches his life-long “psychogeographic” project of a cognitive mapping of the psychological effects produced on the perceptive human consciousness by physical environments. The two axes delineating this mapping are Sinclair’s experiences as an assistant gardener with the Parks Department of an East London borough, and the “sacred landscape” delineated by the churches of Nicholas Hawksmoor. “The most notable thing that struck me as I walked across this landscape for the first time,” he recalls in conversation with Kevin Jackson, “were these run-down churches, and I suddenly realised, there’s this one here and that one there, and maybe there is some connection. And then I did have this very vivid dream of St Anne’s, Limehouse…” (V, 98). One is struck, in turn: “a vivid dream”? “Maybe some connection”? More often than not, Sinclair’s progression in his cognitive mapping is one of “that was my hunch: confirmation followed” (LH, 28). In this, as in much else, Sinclair consciously positions himself as heir to the ancient Celtic tradition of the poet as soothsayer, of the bard whose word, governed by prophetic intuition, has the power to alter reality. As he confided to Jackson,

By nature and temperament I’m absolutely one of those mad Welsh preachers who believes that… deliver a speech and you’ll change someone’s life. Or kill them. I really believe all that, but I can’t go around spouting that and survive, so I’ll adapt equally to the Scottish side of me, which is cynical, rational and cynical, and I believe in that as well. […] It’s Stevenson, the classic Scottish Jekyll and Hyde thing. One is really deranged and manic, the other is looking at it being deranged and manic, and commenting on it. That’s the tension. (V, 59)

Sinclair’s walk around Hawksmoor’s London churches in Lud Heat reveals a “web printed on the city and disguised with multiple superimpositions,” a web “too complex to unravel here, the information too dense: we can only touch on a fraction of the possible relations. […] It is enough to sketch the possibilities.”[7] Drawing upon Alfred Watkins’ theory of the ley line, according to which the ancient sites in England and Wales are aligned with one another in a network of straight routes of communication, Sinclair creates willed ley lines across a chosen area (in Lud Heat, this produces a “hieratic map” of London), which generate a wealth of occult materials in his texts for Sinclair to carefully counterpoint with local, matter-of-fact accounts.

That the ley line is one of Sinclair’s signature tropes has been amply demonstrated in the many prose works that followed Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge. Here, three examples will suffice. His 1997 Lights Out for the Territory, a collection of nine loosely collected perambulatory pieces, describing lighting out for various London nooks both familiar and unfamiliar, forgotten and re-remembered. As Sinclair himself reveals halfway through, the seemingly random extravagations actually serve a specific purpose – his project of map inscription:

Each essay so far written for this book can be assigned one letter of the alphabet. Obviously, the first two pieces go together, the journey from Abney Park to Chingford Mount: V. The circling of the City: O. The history of Vale Royal, its poet and publisher: an X on the map: VOX. The unheard voice is always present in the darkness.[8]

Revisiting his ley-line approach as late as the opening of his 2001 novel, Landor’s Tower—in which the story of a historical figure, Walter Savage Landor, is interwoven with Sinclair’s frustrated attempts to write a book about Landor, along with a subplot about booksellers hunting for rare editions—Sinclair encapsulates Watkins’s lesson in the following formula: “everything connects and, in making those connections, streams of energy are activated.”[9] Later, Sinclair makes it explicit that his use of Watkins’s psycho-geographical concept is a continuation of the modernist poetics of juxtaposition and collage:

All of it to be digested, absorbed, fed into the great work. Wasn’t that the essence of the modernist contract? Multi-voiced lyric seizures countered by drifts of unadorned fact, naked source material spliced into domesticated trivia, anecdotes, borrowings, found footage. Redundant. As much use as a whale carved from margarine, unless there is intervention by that other; unless some unpredicted element takes control, overrides the pre-planned structure, tells you what you don’t know. Willed possession. (LT, 31)

A recent and compelling example of semi-non-fictional accounts of Sinclair’s voyages outside of London is his 2005 Edge of the Orison, which, encompassing the genres of memoir, biography, art theory and literary criticism, follows the journey of the poet John Clare, who, in 1841, having escaped from a lunatic asylum in Epping Forest, walked for three days to his home in Helpston, (then) Northamptonshire, some eighty miles away. In obeisance to his aesthetics of free association and imagist juxtaposition, Sinclair uses the fact that Clare spent his last years at the Northampton asylum, and the coincidence that his journey to Helpston took place in pursuit of his first love, a certain Mary Joyce, to draw a ley line between his central quest and the chronicling of Lucia Joyce’s institutionalisation at the same venue, 110 years later. Enough material for Sinclair’s mind to begin its connect-work:

What happened to Lucia Joyce in Northampton? Can her silence be set against Clare’s painful and garrulous exile? Visitors came to the hospital to pay their respects, to report on the poet’s health. Biographers of Lucia cut out, abruptly, after she steps into the car at Ruislip and drives north, never to return.[10]

According to this logic, Joyce surfaces in Sinclair’s musings at the most unexpected instances. For example, upon pondering the river Lea, Sinclair’s mind makes the sudden Imagist switch to:

Djuna Barnes, profiling James Joyce, zoomed in on his “spoilt and appropriate” teeth. And that is this stretch of the Lea, precisely: spoilt and appropriate. Hissing trains. […] “Writers,” Joyce told Barnes, “should never write about the extraordinary, that is for the journalist.” But already, she was nodding off. “He drifts from one subject to the other, making no definite division.” (EO, 141-2)

At a Northampton hotel, Joyce even enters into Sinclair’s dream in what is an obvious parody of Stephen’s dream of the wraith of his dead mother:

In the Northampton ibis, I dreamt; re-remembered. The drowning. Weaving back, no licence required, on my motor scooter: to Sandycove, the flat beside Joyce’s Martello tower. Wet night. A tinker woman had been pulled from the canal. Drunk. The smell of her. My first and only attempt at artificial resuscitation, meddling with fate. Met with: green mouth-weed, slime, bile, vomit. Incoherent pain. Language returns, curses. Better left in water was the consensus of other night-wanderers: “Leave her be.” World of its own. Woodfire on wasteground within sight of a busy yellow road. Bring someone back from death and you’re landed with them. (EO, 234)

Sinclair’s Joycean re-remembering is complete with its Martello tower setting, its textual echoes, its linguistic (cf. the agglutination “woodfire on wasteground”) as well as narrative (interior monologue) markers. When Sinclair reveals that his first meeting with his wife Anna in 1962 took place in Sandymount, dreaming becomes re-remembering. The “drowning” here is Lucia’s – which brings up another tangent, another ley line, pointing toward Beckett:

James Joyce (always) and Beckett (at the beginning) constructed their works by a process of grafting, editing: quotations, submerged whispers. Correspondences. Joyce read other men’s books only to discover material useful to his current project. Libraries were oracles accessed by long hours of labour: at the cost of sight. The half-blind Beckett, aged twenty-two, reading to a man in dark glasses (waiting for the next operation). A theatrical image reprised in Beckett’s play Endgame. (EO, 234-5)

Memories of Joyce’s photographs become submerged in Sinclair’s reveries about his male ancestors: the memory of “magnifying glass over etymological dictionary: blood-globe, headache. More wrappings around Joyce’s head than a mummy. Bandages under grey Homburg, smoked glasses. Stub of period moustache, just like my father” segues into memories of footage of his soon-to-die grandfather: “This man, a doctor, is very tired. He performs a reflex ritual, perhaps for the last time: remembering how to lift an arm. A moment that parallels Gisele Freund’s 1938 photograph of Joyce in a deckchair. More dead than alive. Moving image showing to a still: bleaching to nothing” (EO, 235). Here as elsewhere, Joycean reminiscences serve Sinclair the purpose of revisiting and coming to terms with his own past.

“Drowning” is the metaphorical ground for the following flights of Sinclair’s metaphorising fancy. Having already observed earlier that “[o]ne of Lucia’s cabal of expensive doctors, Henri Vignes, prescribed injections of sea water. To no evident effect” (EO, 235), Sinclair establishes the following line:

In mid-England, mid-journey, flying and drowning become confused. Drowning and writing. Dreaming and walking. Finnegans Wake: Lucia searching out words for her father, the book for which she is the inspiration. The problem. […] Joyce, fond father, continued to believe that Lucia, dosed on sea-water, would swim back to him, to health. Hospitals taught her to breathe underwater. […] She visited Jung. He couldn’t help. There was an unresolved argument with the author of Ulysses: a book that dared to trespass on his territory. […] “If Joyce was diving into a river,” Jung said, “Lucia was falling.” Voluntary or involuntary immersion: it depends on who is telling the tale. (EO, 235-6)

Sinclair here bypasses the common “anxiety-of-influence” drama of literary ancestry, undermining Joyce’s authority by identifying himself not with Joyce’s fictional alter ego Stephen, but with his real-life, silenced and traumatised daughter Lucia.

Again, Sinclair turns to reminiscences (re-inventions, he calls them) of his own family, adding to the already established network yet another layer: remembering his aunt in Ballsbridge, Sinclair recalls that she had a connection with Beckett, whose lectures in Trinity she attended. Then, Sinclair pulls the final chef-d’oeuvre rabbit out of his magician’s hat of magical correspondences: “When Beckett arrived in Paris, he carried a letter of introduction to Joyce, written by Harry Sinclair. His Aunt Cissie (mother’s sister) married William ‘Boss’ Sinclair” (EO, 241). Finally, towards the end of the journey, Sinclair pays his respects to Lucia when passing Kingsthorpe Cemetery. Ever on the lookout for the aleatory epiphany, before making the turn, “up the slope to where Lucia is buried, I find a nice marker, the grave of a certain Finnegan” (EO, 347).

The ley-lines between Sinclair’s psychogeographic aesthetics and Pound’s Imagist project developed into the “profounder didacticism” of The Cantos working through “revelation” (SL, 180), although perhaps less explicit, are nonetheless equally important for Sinclair. Whether one takes the young 1913 Pound by his word that image is “that which presents an intellectual and emotional complex in an instant of time,”[11] or gives more credence to the post-Imagist Pound of a 1916 letter to Iris Barry, where he associates Imagism with “the actual necessity for creating or constructing something; of presenting an image, or enough images of concrete things arranged to stir the reader” (SL, 90), Sinclair’s divinatory project of decoding, transcribing, and re-presenting the occult cultural memory of a landscape fits both bills. As Robert Sheppard pointed out, Landor’s Tower’s self-description as a record of “multi-voiced, lyric seizures countered by drifts of unadorned fact, naked source material spliced into domesticated trivia, anecdotes, borrowings, found footage” (LT, 31), actually seems to describe Sinclair’s Lud Heat as well as “a work like Pound’s Cantos”:

Pound’s technique of modernist juxtaposition and the ideogrammic method of the Cantos can be read as a literary equivalent of the ley line. Pound states that the juxtaposition of elements without syntactic linkage, by simple contiguous arrangement […] creates new combinations.[12]

When speaking of the genesis of Lud Heat, Sinclair himself, although not invoking Pound directly, likens its composition to “cutting” down and through a “huge Waste Land collage” – a metaphorical parallel to Pound’s real-life creative activity:

because I started on mock-epic forms, like the huge Waste Land collage poem at film school, and I’d written some things in Dublin which were on a large scale, and I weeded all that out. Cut, cut, cut, till I was happiest with these small, fragmentary forms. That seemed to suit the pace of the life. Film-making was exactly the same: single frame, just click click click click… Getting everything down in a very sharp way. Writing and film were part of the same thing. […] I wanted to move […] to a more narrative base, a sense of a man in the world, and what happens in this room, it’s all right in front of your nose. And then I moved back from that, later, into the London mythology. (V, 87)

However, one need not settle for such metaphoric and indirect confirmations of one’s hunch – nor for one of the section subtitles, “Vortex of the Dead! The Generous!” (Lud Heat, 96), which cannot be regarded as a solid, unequivocal intertextual line between the two. The confirmation, as always with Sinclair, comes later, in the twin-piece of Lud Heat. Suicide Bridge, which is subtitled A Book of the Furies/A Mythology of South & East and which, even though published only in 1979, was created simultaneously with its precursor. Its cognate character is evident both formally (a collage text of essayist prose, maps and free verse) as well as thematically: Suicide Bridge covers much of the same ground as Lud Heat, but here the mythological strata are clearly foregrounded and multiplied. The London landscape becomes peopled with Egyptian deities, cabbalistic symbols, characters from the Blakean “Albion” mythology, pop-cult figures Aleister Crowley, Howard Hughes, or JFK, but also host of 1960s countercultural icons: Wilhelm Reich, William Burroughs, Norman O. Brown, the Situationist International. The approach to this welter of information, again, is one of evaluative decoding based on the energy emitted (or, “admitted”) by the system:

An impenetrable maze of statistics, lost in space & time; dead ends, false corridors, pits, traps. All that matters is the energy the structure admits. Can it heat us? Is it active? Or simply a disguise for the lead sheet imprisoning the consciousness of the planet; the gas of oppression, the burnt-out brain cells, milk-centred eyes. (LH, 241)

One of the more energetically rewarding burnings-out of brain cells has taken place earlier on in the text. In the “Kotope: Down the Clerkenwell Corridor” segment, the link sought is one between Pound and the Cathars. To that end, the ancient practice of bibliomancy—of divination in which advice or predictions of the future are sought by random selection of a passage (usually from a sacred text)—is invoked, and the revelation is the following:

no reference Davie (Ezra Pound: Poet As Sculptor)

no reference Dekker (Sailing After Knowledge)

must be Kenner, no alternative,

flip open the great black book itself

& immediately confront:

“O Anubis, guard this portal

as the cellula, Mont Ségur.

Sanctus

that no blood sully this altar”

Kotope is not amazed, that smile,

the head turning,

minions have to react: awe

a magician,

this is it, & Anubis too

the jackal-headed one,

guardian of the mysteries

so lightly approached

(Suicide Bridge 178)

The passage quoted is, of course, “Canto XCII” of the Rock-Drill section of The Cantos, devoted to charting the genealogy of the “true” religious tradition, i.e. the Neoplatonic alternative to mainstream Christianity, bridging the millennium of the Dark Ages and connecting together Antiquity with Early Modern period. The question, as always, for Sinclair, is that of interpretation of the discovery:

for Wilson a simple matter:

mind discovering its power potential,

what you need you get;

for Kotope, the Way

“The four altars at the four coigns of that place,

But in the great love, bewildered

farfalla in tempest

under rain in the dark”

for the servants a Master

rediscovered

we must begin again: ROCK-DRILL

(LH, 179)

There is, however, the ultimately more relevant aesthetic affinity between Pound and Sinclair that lies deeper than intertextual linkage or acknowledged succession. Sinclair’s oeuvre as a whole grows out of an awareness of the interrelatedness between the forms and rhythms of poetry and prose. And if Sinclair (after the decade-long hiatus that followed Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge) turns to the prose medium and novel genre proper, revisiting poetry only sporadically (most recently, in his 2006 collection, Buried at Sea), his prose—according to the consensus among the many of his critics—is endowed with the richness, polyvalence and complexity usually described as “poetic.” Thereby, he follows in the footsteps of Pound’s early remarks from a 1915 letter to Harriet Monroe that “poetry must be as well written as prose. Its language must be a fine language […] There must be no interjections. No words flying off to nothing […] Rhythm must have a meaning. It can’t be merely a careless dash off […] There must be no clichés, set phrases, stereotyped journalese” (SL, 48-9). Sinclair only reverses this process: writing prose as well as poetry, turning to book-length “novels” by extending the prose sections of his poetry, yet carefully eschewing any automatism, cliché, set phrase or stereotype: “making it new” with every image.

David Vichnar

[1] James Joyce, Selected Letters, ed. Richard Ellmann (New York: Viking Press, 1975) 191.

[2] James Joyce, Finnegans Wake (New York & London: Faber & Faber, 1939) 301.

[3] The Selected Letters of Ezra Pound, 1907-1941, ed. D. D. Paige (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovitch, 1950) 7 – all further references are to this edition, marked as SL.

[4] Ezra Pound, Cantos (New York: New Directions Books, 1996) 522.

[5] The Verbals – Iain Sinclair in Conversation with Kevin Jackson (Tonbridge, Kent: Worple Press, 2003) 26 – all further references are to this edition, marked as V.

[6] Robert Bond & Jenny Bavidge, “Introduction,” City Visions: The Work of Iain Sinclair (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2007) 1.

[7] Iain Sinclair, Lud Heat and Suicide Bridge (London: Random House, 1995) 16-7 – further references are to this edition, marked as LH.

[8] Iain Sinclair, Lights out for the Territory (London: Granta, 1997) 156.

[9] Iain Sinclair, Landor’s Tower: or The Imaginary Conversations (London: Granta, 2002) 2 – further references are to this edition, marked as LT.

[10] Iain Sinclair, Edge of the Orison: In the Traces of John Clare’s Journey out of Essex (London: Penguin Group, 2005) 233 – all further references are to this edition, marked as EO.

[11] Ezra Pound, “A Few Don’ts by an Imagist,” Poetry (March, 1913), reprinted in “A Retrospect,” Literary Essays of Ezra Pound, ed. T. S. Eliot (New York: New Directions, 1935) 3.

[12] Robert Sheppard, “Everything Connects: The Cultural Poetics,” City Visions, 34.

Published by Equus Press.

published: 7. 8. 2016