A hundred years have passed since one of the most explosive political events of the 20th century. The Russian Revolution of 1917 remarkably changed the social and political order in

DOX Centre for Contemporary Art brings the presentation of different perceptions of the revolution with the exhibition “1917 – 2017” from Oct. 27 to Jan. 8, 2018.

The whole project started with a competition, where the Russian curator Sergei Serov contacted over seventy graphic designers and artists from different parts of the world to express their views of the event through posters. The idea caused a huge interest, and more than 1500 works from 50 countries were submitted. One hundred selected works will be presented at the

Artists have expressed their opinions in different ways; however, most of the artists portrayed the event negatively. Violence, chaos, and death are equated to the revolution in the artists’ presentations. According to the DOX gallery, only 4 % of works from

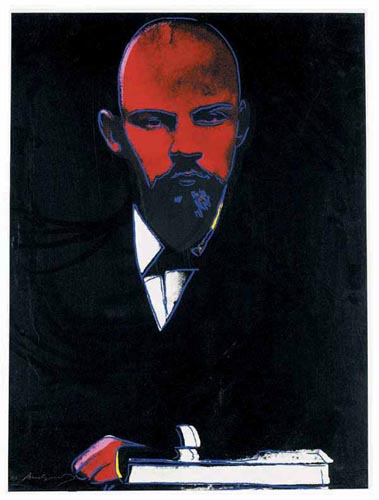

Every poster in the exhibition has three colors: black, red and white, and this combination is obvious. Historically, the red and black flag has been used by anarchist communist movements, where black represents anarchism, and red represents leftist ideals. White and red colors together can also be symbolic for Russians. The White movement, also known as just the Whites, was active in

The majority of the posters appear unusual as they are made in the style of the Russian avant-garde, reminding viewers of the revolution agitation posters of the era. Maryia Hilep’s poster of Lenin with red laser eyes greets visitors at the entrance. Many works display a hammer and sickle, the communist symbol which appeared during the revolution. The red star, a symbol of communism after the October Revolution and during the 1918 – 1921 civil war in

On a couple of posters, a parallel is made between Lenin and the current Russian president Vladimir Putin. Anton Batishev’s poster features a face combined from the halves of Lenin’s and Putin’s faces. Similarly, the poster by the Russian artist Evgeny Moryakov mixes the faces of these two leaders.

In general, the posters are sarcastic in some way or another. Such works as Polina Parygina’s “Monster of the Revolution”, or Nikolai Raev’s “Everything is for the Children” with the evil face of Lenin show that the revolution is associated with fear, blood and suffering.

Another provocative poster has Lenin and the widespread saying in

Besides the posters, the exhibit includes “My Russian Flag” by the contemporary Russian artist Anton Litvin. His flag is hanging on the wall, however, it differs from the common flag of

The flag rotation is a reaction to the crimes of Putin’s regime, and the wish of the artist to approach

One hundred years since 1917,

Author is a student at the Anglo-American University in Prague

published: 24. 11. 2017