In EXPERIMENTALISM, PART 1, “experiment” was traced back to its etymological connection with “experience” as the process of departing from what has been tested, of gaining knowledge by venturing beyond the known grounds – just as Joyce, Borges and Beckett did in both their lives and fiction.

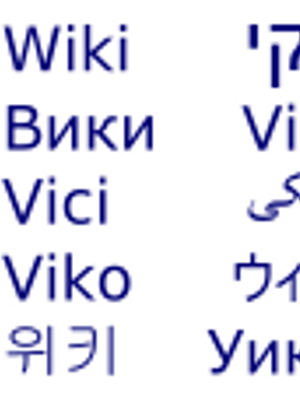

The particular sort of experience engaged with in the fiction promoted by Equus Press has been described as “translocal,” aiming to counter the explicit nationalism of the literary establishment. Contemporary fiction and poetry – even though written in and about a world arguably marked by increasing globalisation and internationalisation – is still very much an endeavour with nationalist underpinnings, this for a whole array of reasons: from linguistic ones (translation as a delay in dissemination, major languages vs. minor languages) to financial aspects (most poetry and arts funding being organised around cultural institutes whose interest is to support writers and artists from their particular nation-states) to institutional function of literature as part of pedagogy (the origins of national literature as a subject of study in schools).

Translocal writing can be best defined as one created outside of its native emplacement and concerned with dwelling, identity, and place as experiences of writing. As such, the most pressing challenge tackled is how to transform its particular placed-based knowledge or insight into a larger, more generalisable idea, to be able to name and use its local, everyday, physical experience without rendering it strange or exotic. A similar dynamic, of course, is found in all experimental writing worthy of its name, but what marks off the translocal category is the degree in which its experimentation is place-bound, whether geographically or linguistically. Writing promoted by Equus Press, written from within and about a cultural space in a language that is not its own entails, almost by necessity, a whole range of variations upon the received dogmas and conventions of narrative, genre, style. In so doing, it is experimental in ways similar to that of modern science, which, whose development, according to John Dewey,

began when there was recognized in certain technical fields a power to utilize variations as the starting points of new observations, hypotheses and experiments. The growth of the experimental as distinct from the dogmatic habit of mind is due to increased ability to utilize variations for constructive ends instead of suppressing them. (John Dewey, Experience and Nature, xiv)

Equus Press aims to further a conception of experimentalism which is conditioned by “a power to utilize variations as the starting points of new observations” and the “ability to utilize variations for constructive ends instead of suppressing them.”

Here, the example is Louis Armand’s 2012 novel, Breakfast at Midnight. As early as page 1, one reads “all I can remember is blackness, the sound of bees, a face staring up at me with eyes full of blood” and a page later,

The way my mother used to curdle milk with lemon juice. Once upon a time, staring up at a plum tree with a white rope of bed linen hanging in it. A vertical line through the foliage and that same smell of soured milk. Grass thick with rotten plums, ants, wasps, fruit flies swarming over them. The sound of bees. A pair of black leather high heel shoes covered in ants. (BAM, 2)

Then, on page 5, “Laughter, like a swarm of bees, swarming closer,” and again later, “Bruised flesh leers pornographic – laughter, like a swarm of bees, swarming closer” (BAM, 11). From these close-up flashbacks, then, a conceptual association emerges, synaesthetically linking together the smell of soured milk, the sound of laughter, of bees swarming, and the sight of a plum tree with a white rope. The nexus of all of these (as well as their trigger in the page-2 quote), is the scene of the mother’s suicide witnessed by the narrator in his young youth, who stares at her shoes “covered in ants,” “trying to connect them to the stockinged feet that hung down between the branches” (BAM, 18). This scene, then, keeps haunting the narrative like the constantly returning repressed: whether at an abandoned La Paz infirmary,

When I opened my eyes again, my mother was hanging in the tree in the middle of the room. An ecstatic fixity of expression on her face. I sat there listening to the flies as her corpse revolved slowly at the end of its rope. (BAM, 65)

Or in the jungle area of the Rio Ucayali:

I lay there, boa constrictor eyes staring down from dead branches. A voice spoke to me. “Once upon a time,” the voice said, without ever getting any further. (BAM, 68)

Or on a bridge in Prague, redubbed Kafkaville:

Under my feet, the bridge casts impenetrable shadows, straight down into an abyss. The sound of rain across the water like the swarming of bees. (BAM, 151)

Armand’s narrative is a carefully construed concatenation of many such image assemblages, montages of leitmotifs recurring in feverish, hallucinatory flashbacks.

The modernist aesthetics of fragmentation is employed together with another staple modernist device – a mythological intertext functioning as a grid by which to structure the narrative. This is evident in its segmentation into 24 chapters (after Ilias and Odyssey) and the fact that its last chapter is set in the eponymous Prague quarter of “Trója” (Czech for “Troy”), as well as in minor motifs: the barge on the Vltava temporarily inhabited by the protagonist is called GORA, an acronym for the fabulous ARGO. His revisitation of past traumas, just as Odysseus’ homecoming, takes place after “ten years of wanting to believe that everything which ends begins again” (BAM, 81). Armand is careful to acknowledge his modernist inspiration in a few intertextual nods to Franz Kafka and James Joyce. Joyce is present both in Armand’s exploration of narrative point-of-view and his constant interplay between external description and interior monologue, as well as in a few specific textual echoes. In one of the early interactions between the protagonist and his Mephistopheles-like mentor and seducer, Blake, one reads “The muscle in Blake’s jaw stands out. Prognathous” (BAM, 24), an intriguing echo of a passage on page 3 of Ulysses: “He peered sideways up and gave a long slow whistle of call, then paused awhile in rapt attention, his even white teeth glistening here and there with gold points. Chrysostomos” (U 1.26). The similarity goes beyond the superficial one of introducing an obscure Greek word – what is at stake is a juxtaposition of impersonal external matter-of-fact observation of a jaw muscle (in Armand) and golden teeth (in Joyce) with an interior voice of the observer. If Joyce famously recast his Dedalus and Mulligan as 1904 Dublin’s Telemachus and Antinous, then Armand does to Joyce what Joyce himself did to Homer, recasting his protagonist and antagonist as Stephen and Mulligan. The Joycean link is strengthened soon after when “the lampshade’s shadow cuts Blake’s face in half, one eye gone black” (BAM, 25), where “one eye gone black” is a borrowing from Finnegans Wake (FW 16.29), but here functionally employed in a setting description.

Franz Kafka, as Armand’s critics have already noted, is thematically present in Breakfast at Midnight via a shared narrative concern with paternity and parricide (the chief intertext being Kafka’s “Letter to Father”). However, there is also a more playfully textual, translingual connection established via the motif of the jackdaw. Its first appearance comes in the Faustian scene of the impossible seizure of the moment:

I think how beautiful it would be to lie there with Regen forever. Free to invent the world. To own the sunrise. To sail ahead of the great deluge, bathed in warm orange light. But somewhere above the crazed music, the laughter and drunken voices, there’s a droning that gets louder and more insistent until it hangs over us like the shadow of a great oppressive black bird, eclipsing everything. (BAM, 72)

The black bird is identified as jackdaw in another scene haunted by the ghost – not of the father, but of the mother, again:

I lie there, watching the clouds merge and separate. A hundred thousand mental images all taking shape in the one space. The sound of water becomes the sound of bees. […] The sky slips on its reel like a piece of celluloid. The image jags. Something dark crosses my field of vision. Black plumage on grey. Jackdaw. I see the bird peering at me. An expressive eye. It opens its beak and leans forward. I realise it’s speaking to me, but I can’t make out what it’s saying. (BAM, 120)

This inability to “make out what it’s saying,” this misunderstanding, stages the translingual content of the jackdaw motif: jackdaw, in Czech, is kavka, the etymological origin of Kafka’s name, itself a misspelling of the Czech ornithological appellation. The jackdaw’s emissions – in a phantasmagorical, LSD-induced scene of a burial mass for a deceased young woman – are, unlike the refrain of Poe’s Raven, not of human language, but “gurgling craw-sounds, words lost in transmission” (BAM, 121).

The drug-induced reality of so much of the narrative, its progression via variations played upon clusters of associated images and leitmotif montages, has earned Armand’s book the genre-assignation of “acid noir” and critical praise for being a “pitch-perfect,” “modern,” “twisted, brilliantly savage” noir, is a translocal text whose self-conscious position between languages and traditions drives its many explorations of words lost in transmission. It is of course not simply a matter of adding local colour to exotic scenes by peppering the text with the odd Spanish slang term in passages set in South America or having a Marais barman exclaim “Travail, Famille, Patrie!” (BAM, 78). It is a matter of creatively reworking the past, whether via parodic echoes (of Joyce) or translingual punning (the kavka/jackdaw motif). It is also a matter of letting the Anglophone reader experience the foreign as the native, as e.g. in the following passage where the seemingly never-ending train journey is staged through an equally never-ending list of local place names:

The train journey seemed as though it would never end. Žerůtky, Moravské Budějovice, Lukov, Bohušice, Popovice, Lesůňky, Horní Újezd, Kojetice, Čechočovice, Hvězdoňovice, Okříšky, Přibyslavice, Číchov, Bransouze, Dolní Smrčné, Přímělkov, Bítovčice, Předboř, Petrovice, Bradlo, Malý Beranov, Hruškové Dvory, Jihlava. Then north, to Havlíčkův Brod, Sázava, Čerčany. The place names multiplied. They flashed past like time itself made visible in a blur of syllables. I began to lose track of where we were and where we were going. (BAM, 53).

It is, ultimately, a matter of writing fiction which is endowed with, to paraphrase Dewey, “the power to utilize variations as the starting points of new observations,” a fiction whose topology is rendered tangible, “visible in a blur of syllables” on the page, without being presented as an exotic curiosity, but something lived and suffered through, to the extreme.

And there has been, and will be, more.

published: 8. 12. 2013