Our featured year-end article explores the dichotomies of the formation of today’s Europe and the conflicts, tensions, and solutions therein.

Europe has a long tradition of self-segregation, of multi-dimensionality, of debates on national identity that can go as far as internal conflict. The first failure of our ‘common home’ was the fracturing of the Roman Empire into a western and an eastern segment. Rome broke away from Byzantium, Catholicism from Orthodoxy, Protestantism from Catholicism, the Empire from the Papacy, East from West, North from South, the Germanic from the Latin, communism from capitalism, Britain from the rest of the continent. We easily perceive the differences that make up our identity; we are able at any time to distance ourselves from ourselves. We invented both colonialism and anti-colonialism; we invented Eurocentrism and the relativisation of Europeanism. The world wars of the last century began as intra-European wars; the European West and East were for decades kept apart by a ‘cold war’. An impossible ‘conjugal’ triangle has constantly inflamed spirits: the German, the Latin and the Slavic worlds. An increasingly acute irritation is taking hold between the European Union and Europe in the wider sense, between central administration and national sovereignty, between the Eurozone countries and those with their own currencies, between the Schengen countries and those excluded from the treaty

The North–South division

‘Don’t forget,’ say the Greeks, ‘that “Europe” is a Greek word, the same as “democracy”, “economy” and “politics”.’ I would nonetheless hasten to add that ‘chaos’, ‘apocalypse’ and ‘catastrophe’ are also words that come from Greek. At any rate, it is obvious that the South has arguments to consider itself the source of European culture, even if what we today call Europe is the result of an evolutionary course that has moved steadily northwards: from Athens to Rome, from Rome to the Franco-German Empire, and culminating with the Industrial Revolution in England.

Modernity is inconceivable without the contribution of the Protestant North. And so the South has the superiority complex of the founding homeland and, at the same time, an inferiority complex in matters of civilisation. But the Anglo-Saxon world also has a complex about the South, which, as Wolf Lepenies says, is the depository of savoir-vivre, to which northerners can counter only with a drab savoir-faire. The North rediscovers the attraction of the South (Drang nach Süden), Goethe indulges in Italienische Reisen, Byron dies in Greece. But the South does not mean only Greece. Among other things, it also means the prestige of Latinity.

On the other hand, if we are moving southward, then we have to go all the way. Let us recover the Near East (with the Syria of John Chrysostom) and North Africa (with the founding theology of St Augustine). Let us revaluate the idea of a Mediterranean Union,

which has always been there, particularly in the French ‘imaginary’, from Saint-Simon to Nicolas Sarkozy. At the same time, let us follow Lepenies’s distinction between legitimate regional consolidation of the Mediterranean space and the arrogant idea of a ‘Latin empire’, which to him quite rightly seems outdated. But to return to the subject of newcomers, what about the Poles, the Hungarians, the Baltic countries, the Romanians (Orthodox Latins), and even the Russians and the Greeks? Will we have to choose between the ‘cultural’ hegemony of Latinity and the ‘civilisational’ advantages of the Anglo-Saxon ‘empire’?

The East–West division

Even if we no longer realise it, we still live in the shadow of the old antagonism between Rome and Constantinople, between the reforming West, the source of modernity, on the one hand, and conservative Byzantium, contaminated by the Slavic and the Ottoman world, on the other. We might say that the Great Schism of 1056 was the first failure of European integration. Historians are in agreement that, after the eleventh century, the West flourished while the East stagnated ‘Byzantine’ comes to be a label for excess, stagnation, and a series of defects: despotism (excessive centralisation), dogmatism, religious intolerance, excessive state bureaucracy.

In 1734 Montesquieu drew a distinction between oriental authoritarianism and the Roman-derived constitutionalism adopted by the West. Also in the eighteenth century, Edward Gibbon painted an unsparing portrait of the East: corruption, depravity, superstition, indolence. The Byzantium described in the writings of Procopius of Caesarea possesses the laxness of vice-ridden femininity, in contrast to the virile vigour of Graeco-Roman antiquity.

The descendants of Byzantium, in their turn, find reasons to condemn the excesses of western rationalism (a blend of Scholasticism and Cartesianism), materialism, anthropocentrism, atheism, and all that western ‘modernity’ and ‘secularisation’ opposes to eastern tradition. In addition, and not without justification, they point out that it was the Byzantines who published the first textbooks of Greek in the West, that the Italian humanists of the fifteenth century salvaged the Greek sources of European civilisation (literature, law, patristic theology) thanks to the Byzantine scholars who had gone into exile in the West after the Ottoman occupation. They also invoke the unfortunate fourth crusade of 1204, which barbarously sacked Constantinople, causing what the great Byzantine historian Niketas Choniates called ‘the deepest rift of enmity’ between the two worlds.

But the two segments of Europe were also cracking within their own borders. In the East in particular, there were, on the one hand, apologists for synchronisation with the West (usually educated in western universities) and, on the other, zealous advocates of Constantinopolitan glory, which survived in what Romanian historian Nicolae Iorga called ‘Byzantium after Byzantium.’ In tsarist Russia, this was also the cause of the conflict between the zapadniki (the pro-westerners) and the Slavophile traditionalists.

In the post-communist countries’ difficult period of pre-accession to the European Union, the general perception regarding their inability to meet the acquisquickly was that they suffered from a deficit of European-ness, explainable simply by their geographical position in the East. In such circumstances, to Europeanise yourself seemed to mean strictly to westernise yourself.

These countries may be European precisely because of their problematic position relative to a certain kind of Eurocentrism. A Serbian student of mine at the New Europe College in

Bucharest formulated the specific profile of the region in highly expressive terms: ‘We are the East of the West and the West of the East.’ It is a description that includes both Romania and all the states of the Black Sea Region and Balkans. Stimulated by this formula, I have tried to analyse the presuppositions of his argument. To be the East of the West and the West of the East might mean the following:

To be both means, as a matter of fact, to be between. Because we take a little something from both directions, we are, it is said, conciliators by vocation; we form a bridge between two separate shores, allowing them to communicate. We are a pivot between Asia and Europe, just as we are a balance between North and South. But at the same time (and, unfortunately, more and more often), this exposes us to the status of a vague territory, of a space of transit, swept by winds from every direction.

A third version of our equivocal position would be neither… nor. We are neither eastern enough, nor western enough. Dumped in a place that is more like a displacement, stalked by opposing temptations, standing indecisively at the crossroads, we are in constant search of our real self, of the best means to elucidate and express our true being. When faced with eastern excesses, then we are westerners. When western rigour is demanded of us, then we pigheadedly take eastern liberties. We therefore experience a permanent syndrome of non-belonging. We have no place. Or rather, we are poorly placed.

Our being the East of the West and the West of the East also means simultaneously feeling a passion for both old and new. Inclining toward the East, we exalt tradition, the ancestral, times immemorial, orthodoxy. But tempted by the West, we seek and idolatrise the new, we aspire to synchronism, adaptation, headlong modernity. The inevitable risk: ‘forms without content’, overhasty borrowing, abusive adaptation. And on the other hand, intransigent conservatism, immobility, opacity.

This also means oscillating between an insufficiently (or incompletely) assimilated West and a repressed but defining East. Either we pose as westerners, provoking rebellion on the part of our non-Latin background (of which we are rather embarrassed), or we pose as Orthodox fundamentalists, causing vague bewilderment on the part of our western partners and creating problems when it comes to European integration.

The centre–periphery division

The question of regional position inevitably brings to the fore the debate about a possible hierarchy – both real and symbolic – between the various European countries. Like in the past, people talk about a Kern Europa, the core, the powerhouse, the driving force, the vanguard of unification, represented by the Franco-German tandem. Economists, philosophers (Jürgen Habermas), and top politicians have put forward substantial arguments in support of this idea. And it would be ridiculous to dismiss it in the name of local pride. We know that Descartes wasn’t born in Sofia and Hegel wasn’t born in Bucharest. We know that in there are few places in the world – and not just in Europe – where there is such prosperity, social stability, and such style. And it is perfectly normal that so complicated and important a historical process as European integration should have a guiding spirit to match. At any rate, the idea is not new: it had venerable proponents as early as the Thirty Years War, and then in Kant, and in Saint-Simon and Thierry at the beginning of the nineteenth century. Correlatively, the idea of a two-speed Europe has also arisen – a concept inevitably not to the liking of those who travel more slowly (even though the idea was not the result of a central decision but due to the inaptitude of some of the travellers themselves).

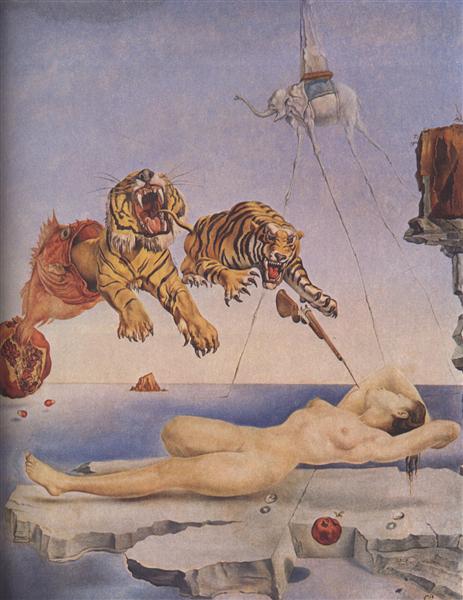

Although realistic in the immediate present, the idea of the core nonetheless has some flaws. The first is of a historical order. The relationship between the centre and the periphery has, over the course of time, proven to be highly flexible and therefore inconclusive. Europe’s first hard core was the Mediterranean space. Then, as we already mentioned, it made its way from Athens to Rome, before making a long sojourn in Constantinople. For a time the hard core was Aachen. In the seventeenth century, the European vanguard meant Louis XIV, and in the century that followed it was England, with the Industrial Revolution. In 1815, the essential Europe was equivalent to the Holy Alliance, uniting a Catholic Austrian dynasty, a Protestant Prussian dynasty, and a Russian Orthodox dynasty. Italy has had its great moments (the Renaissance), and so too did Spain and Holland. And it remains to be seen what the hard core looks like now that EU enlargement has brought with it two hundred million new Europeans (central, eastern, and south-eastern). Viewed historically, Europe looks less like a schematic apricot and more like a pomegranate, with multiple cores. In absolute terms, as Pascal said, the centre is everywhere and the circumference nowhere. There is a Latin Europe and an Anglo-Saxon Europe, a Catholic Europe, a Jewish Europe, a Protestant Europe, an Orthodox Europe, and lately, whether we like it or not, a Muslim Europe.

The idea of a European core also has a psychologicaland strategic disadvantage. The ‘marginals’ can declare themselves demotivated. They feel they are perceived as a sort of background noise, with very distant prospects for real integration. At best, they are uninvited guests condescendingly tolerated at the core table. Not to mention that the psychology of the excluded quickly turns to resentment if it does not become placidity. At the margins, there are always plenty of people who can hardly wait to indulge in the voluptuousness, the torpor, the irresponsibility of marginality. They can hardly wait for somebody to tell them that they don’t have to get involved, that everything is decided elsewhere, somewhere at the top, in the blinding light of the core. Indeed, once the door of derision has been opened, we will be tempted to view the whole of the European continent as a minor province on the world map. ‘A peninsula of Asia’, as it amused Paul Valéry to say…

After this collection of divisions, historical and stylistic tensions and hysterical emphasis on differences, we might be tempted to become Eurosceptic, if not downright depressive. But that was not my intention. On the contrary! All the while I have had in mind the benefits of diversity, the seductive vitality of an organism that defies systematisation, that rejects geometrical homogenisation. We don’t want a Europe of exclusion, regimentation, ethnic and ideological purity, crucified alterities. Such an evolution would lead to the ‘thermal’, entropic death of our solidarity. We prefer a complicated Europe to a triumphalist ‘mantra’, incapable of ever entering into discussion. The Europe to which we adhere is the Europe that founded anthropology, the discipline of understanding cultural difference; the Europe that dedicated itself to the study of savage thought, that filled its universities with departments for the study of non-European languages and civilisations. We often forget that the history of modern Europe began with the improbable encounter between a decaying Roman Empire and invading nomadic tribes from Asia. We are the product of that spectacular hybridisation. This perhaps explains our openness to everything that does not frame us within a static identity

Yes, the European Union has ‘the fragility of all things political,’ as Ivan Krastev says somewhere. Yes, Jacques Delors was right to fear that in our endeavour to construct a community, we might become a kind of UPO: ‘an unidentified political object’. Yes, we might join Tony Judt in saying that ‘Europe is more than a geographical notion, but less than an answer’. Yes, even in the late 1980s, Hans Magnus Enzensberger had fears about the post-democratic evolution of our ‘gentle monster from Brussels’. As we know, there are severe cracks in democracy, capitalism and globalisation. Nationalism is no longer an arrogant vestige of provincial Europe, but a successful electoral weapon in the continent’s centre. We are faced with Brexit, Turkey, refugees, terrorism, Crimea, financial crises, and more. But the solution is neither deconstructive panic nor the rosy demagogy of a luminous future. Throughout its existence, Europe has been trained to survive, to integrate its fractures, to transform its scars into signs of life. It was of the advantages (and the charm?) of a seminal disorder that Michael Portillo, the British Minister of Defence between 1995 and 1997, was probably thinking when he said, ‘I am very much in favour of an untidy Europe. I’m hoping that apart from being good for the new democracies, enlargement will create an untidier Europe.’ If I am not mistaken, we are very close to achieving this goal.

This article is a transcript of Andrei Pleșu’s speech given at the Institute of Human Sciences, Vienna, on 9 June 2017. It is a shortened re-print from the first Eurozine publication of Feb 19, 2018. Andrei Plesu is a renowned Romanian historian and philosopher.

published: 27. 12. 2018