Quinsy Gario

Carnival is a time of cultural exuberance. In the Low Countries, however, the masquerade has become a refuge for dominant groups to caricature the heritage and bodies of others. Where does this propensity come from? And can it be changed?

It’s post-carnival, but any hangovers in the Low Countries today aren’t a mark of the usual physical overindulgence. This year’s carnival festivities were cancelled. Yet questions still remain about last year’s mayhem and the celebration’s cultural leftovers.

Carnival 2020 resulted in an initial northern European coronavirus hotspot. As the healthcare system in Bergamo collapsed, those who had only just returned from their skiing holidays in Italy decided to celebrate carnival in North Brabant. They simply could not miss the annual event: the fun of people closely packed together, the beer, the carnival songs easy to holler along to, the gaudy costumes.

Now, the decision to seek out more crowds after having just visited a hotspot would raise many questions. However, at the time, it was somewhat dismissed – political leaders in the Netherlands even encouraged people to go out and party.

The outbreak that followed in North Brabant was initially largely ignored by the rest of the Netherlands. Its occurrence south of the rivers made it seem as though it was happening in another country – at least according to those at the nodes of newsgathering and public opinion. A racist carnival song even appeared in the Netherlands that linked the virus’s outbreak to dining in Chinese restaurants instead of skiing in the Alps – and people call this humour.

Carnival songs have recently been in the news more often in the Netherlands than I am used to in the Caribbean and not because they ridicule the dominant group. These songs treat different groups and individuals disparagingly based on their race. Dutch politician, actor and presenter Sylvana Simons, for example, was once pressured to ‘pack her bags’ because of her criticism of racism within the Netherlands. The song was followed by a lynching video. Although carnival seems to be an increasing cover for racism, it could also be the means of liberation from that racism.

The Antillean carnival

The Antillean carnival demonstrates that carnival can be a celebration of liberation. After all, the festival’s experience in North Brabant is indeed different from that on the island of St. Maarten, where I grew up. There, it developed after liberated Indigenous peoples emphatically changed the context of that previously hosted by European colonists. While for the islands’ white elite carnival was initially an exclusive party with masks, various groups took the form, imitated elements and supplemented it with local rituals, reflections and African rhythms – adaptations that the plantation owners had always forbidden. Only after the anti-colonial uprising of 30 May 1969 was carnival officially allowed on Curaçao. Now, it is an indispensable part of the region. Going as a child to Carnival Village on the Pondfill in St. Maarten’s Philipsburg was more than a family outing – it was a way to watch a community celebrate its diversity.

However, few people know or remember that the first Antillean carnival in the Netherlands was organized in 1982. The prices of airline tickets to the islands that the Dutch had colonized and occupied became so expensive due to the oil crisis that the Antillean community in the Netherlands decided to organize its own version. In 1982, groups from Den Helder to Tilburg went to the Antillean carnival in centrally located Utrecht hosted by cultural association Kibra Hacha.

Kibra Hacha, named after a Caribbean tree that only blossoms once a year, unites members who, for various reasons, arrived in the Netherlands from Curaçao, Aruba, Bonaire, St. Maarten, St. Eustatius and Saba. When I went to study in Utrecht in 2002, I took part in the association’s orientation week in a suburb called Zuilen; the centre had already been driven from the city centre due to rent hikes. Since then, Kibra Hacha has also lost that location and its Facebook page has been inactive since 2011.

The association’s role in establishing and organizing the Caribbean version of carnival in the Netherlands has more or less been erased from Utrecht’s history as well. After two consecutive editions, the carnival was moved to Rotterdam in 1984 and renamed Zomercarnaval. Having become part of Rotterdam’s official marketing and identity, its activist origins have faded into the background.

Hostility and theft

The role that migrant communities can play in public events is indicative of societal progress. It shows what the dominant community thinks regarding who belongs and how they earned their place. In 2010 Aalst’s carnival was placed on the UNESCO World Heritage List. However, society can also regress: ten years later, in February 2020, the carnival was removed from the listing after a refusal to ban racist and anti-Semitic stereotypes from the parade.

Less extreme examples of unchecked power and dominance in folkloric festivals and parades also exist. For example, the Ommegang parade, organized once every twenty-five years in Mechelen, underwent significant change in 2013 when organizers added new characters to the parade of the giants, otherwise dominated by white characters dressed in eighteenth and nineteenth-century garb: an African, an Asian and an Arab character. The Ommegang took place at the same time as Contour, the Mechelen Biennale. One of its participants Swedish artist Petra Bauer collaborated with artist and writer Annette Krause to make Read the masks, tradition is not given about the blackface tradition Zwarte Piet (Black Peter). When she heard about the Ommegang, she decided to follow the creation process of these new characters.

Among other things, she set up a series of interviews with the individuals involved, including designers, garment makers, members of the sounding board group and the organization’s director. She sent transcripts to a number of people, including myself, to reflect on them for Choreography for the giants, a book which would consist of Bauer’s interviews and correspondence supplemented with critical commentary by guest contributors. I gave up after reading just a third of the transcripts. It was admittedly commendable that the organizers of a centuries-old public event finally wanted to show racial diversity, but the stereotypical thoughts expressed were not only naive but also aggressive. I was exhausted by the unashamedly exuberant display of white hostility.

Attempts to rectify colonial harm inflicted on Indigenous peoples may be worthy but only when done the right way. In 2017, for example, choreographer Ezster Salamon presented the dance performance Monument 6: Landing a ritual of empathy at Wiels during Kunstenfestivaldesarts, which she described as a re-enactment of a lost dance of the exterminated Mapuche. But this wasn’t right at all. In a letter published in February 2020, Moira Ivana Millan from the Movement of Indigenous Women for Buen Vivir called it ‘revolting’. Indeed, in my opinion, Salamon is rightly referred to as a ‘neo-pirate’: the Mapuche still exist and the choreographer knew about the dance because it had been secretly recorded. The re-enactment of the dance, though stripped of its spiritual meaning, is an active participation in the centuries-long colonial effort to eradicate the Mapuche and extract their knowledge from its local context.

Colonial scenes

Carnival in the Low Countries and elsewhere in Europe treats other cultures with indifference. Actually, I do not even know if I should still describe it as ‘indifference’: after all, indifference suggests that something is not thought about for too long, while, in this case, the choices being made actually derive from a deep reservoir of ideas about the other. The cultural archive is drawn upon and embedded, as described by Gloria Wekker in her book White Innocence.1

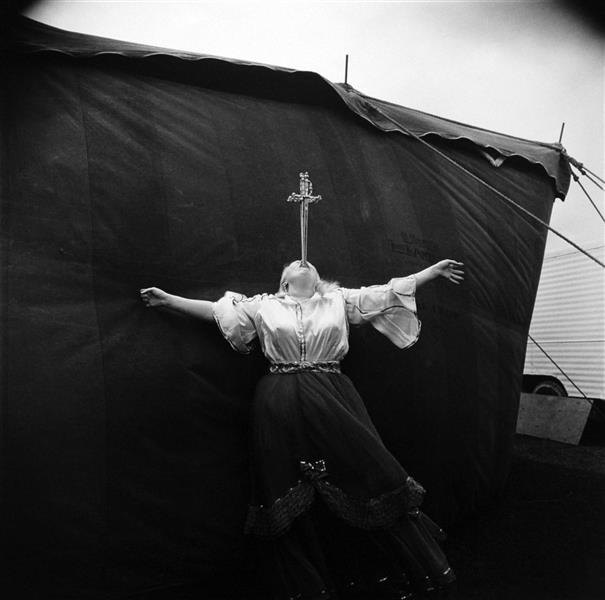

In addition to people who dress up as fantasy characters or represent professions, there are those who use the opportunity to appropriate the costume, skin colour or attributes belonging to the spiritual ceremonies of cultures from all over the world. White Europe seems to have an insatiable urge to exercise dominance over communities that it does not consider its own.

It is crucial that we gain more insight into these types of practices. Carnival could be the place to raises awareness of exactly this kind of theft so that individuals and organizations involved do some soul searching with regard to their participation in cultural appropriation. The public event could be a revolutionary space in which dominance is rejected and abuses are addressed. Unfortunately, it is still too often a place that presents the other as a caricature. It is precisely these entrenched colonial models that Indigenous groups try to break through by means of public demonstrations and parades.

The presentation of the other as proof of progress is nothing new. In 1958, the World Expo took place in Brussels, exhibiting the reconstruction and wealth of Europe. It occurred a year after the independence of Ghana, the first African country to fight for its freedom, and one hundred and forty-five years after the independence of Haiti, where the enslaved successfully liberated their own nation for the first time. The Expo was an extremely colonial production. It presented Europe as an advanced continent that was well ahead of colonial territories in its technological development. The territories were placed outside of human history by means of racist and caricaturized representations in, amongst other things, human zoos. People were displayed in living show-boxes as if frozen in a time that Europe had, so to speak, long since left behind. The racist colonial scenes emphasized the wealth and power of white Europe without noting that the wretched situation in the colonized territories was precisely the result of European violence and theft.

Now that colonial institutions are dying out, the urge to create public representations of the powerless living other is growing. It is no coincidence that one of the first major events at Tervuren’s Africa Museum after its reopening in 2018 was contentious. White people shamelessly went to Thé Dansant’s Afrohouse party in blackface and clothes made from Vlisco fabric. The museum and organization kowtowed to the wider public after even media outlets like CNN reported on it. This was not an isolated incident. While museums like the Africa Museum have given themselves the impossible task of decolonizing, there is a whitelash going on against the dismantling of similar colonial institutions. Even the current production of carnival, where the embodiment of the other is frequently racist and caricatured, is also inextricably linked with the removal of colonial representations from museums and other public spaces. It is a defensive response by white people to the dismantling of racist systems.

A time of liberation

When we repeat actions often enough, they become rituals to which we attribute personal and communal meanings. Old colonial power dynamics are anchored in our present time through repetition. Groups that have enforced dominance through violence demonstrate their accumulative power to caricature the heritage and bodies of others. This dominance is celebrated consciously and unconsciously.

Coming from the Caribbean, which was colonized by representatives of the Republic of Seven Provinces, I both do and do not belong to the European, Dutch and Belgian community. I am ‘surplus’ to the occupation and exploitation of a region that dehumanized people by enslaving them and violently forcing them to mine resources and grow crops. Remaining vital, in spite of all this, is the rejection of an imposed fate. Carnival in the Caribbean region was born out of this urge to transcend occupier invented roles. Our customs and rituals were explicitly characterized as the opposite of normal, respectable and decent behaviour. The roles imposed by violence, religion and policy, which were repeatedly seen in all aspects of society, could be cast off during carnival. It was precisely through the search for space within and outside the system that carnival became an important celebration of liberation from colonial white domination. Carnival still takes place within a Catholic framework yet is supplemented by a mixture of influences and references.

Carnival in Europe must reincorporate that resistance to assumed roles, behaviour imposed out of the need for dominance. Currently, the festival is experienced as a time when everything is allowed and everything is possible. Yet the question that has to be asked is: at whose expense? The introspective dimension inspired by religious beliefs has been eroded or has disappeared for the majority of carnivalists.

The festival is also no longer used to display and cherish diversity within the community. In the Low Countries, there are countless examples where difference is not celebrated but stigmatized and placed under suspicion. Individuals in a culturally, socially or politically dominant position attempt to go back to a time where their cultural superiority was unquestioned. As the history of carnival shows, it is the perfect place to respond to these dominant groups. If we do not want to see the festival lost to corona virus, reactionaries or racists, we better do everything we can to save it.

This article was originally published in the Belgian journal Rekto:verso, issue 89 (2021).

This article is taken from the source: EUROZINE

published: 4. 3. 2021