Philipp Ther

Germany was quick to claim the German-Turkish vaccine developers of Pfizer/BioNTech as proof of its open society. But their success is more an exception than a rule. Rather than congratulate itself, Germany needs to confront how it abandoned the migrants it once invited.

Crises are widely perceived as perilous and many people find them deeply unsettling. Yet they can also trigger positive change. The Covid-19 pandemic is no exception. In recent months, the German Federal Republic’s meritocratic society has seen the emergence of a new myth, best summarized as ‘the child of guest workers to billionaire-cum-life-saver’ narrative. The tale it tells is reminiscent of the ‘from dishwasher to millionaire’ promise made by capitalist modernity. This American fable may not be very well-supported sociologically, but it has long been behind the fascination which the US used to exert worldwide.

Both stories of upward social mobility are immensely powerful. They build on a deeper matrix within western culture: on hundreds of coming-of-age novels, in Germany from Günter Grass to Erwin Strittmatter, and ultimately also on biblical narratives. From small beginnings, the millionaires and billionaires of the modern era ennoble themselves through their ascent. They become the myth bearers of meritocracy, strengthening a fundamental promise of liberal democracies: that individual performance determines social position.

As we know from tales of ancient times, people can break under the burden of myths they supposedly embody. It was wise of the couple who developed the COVID vaccine – Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci – not to allow themselves to be drawn into the kind of personal details that tabloid newspapers and gossip magazines would have lapped up. The team have volunteered only scant information about their private lives. The public knows that their families came from Turkey; that they went to school in Germany, studied there and subsequently succeeded as scientists and entrepreneurs.

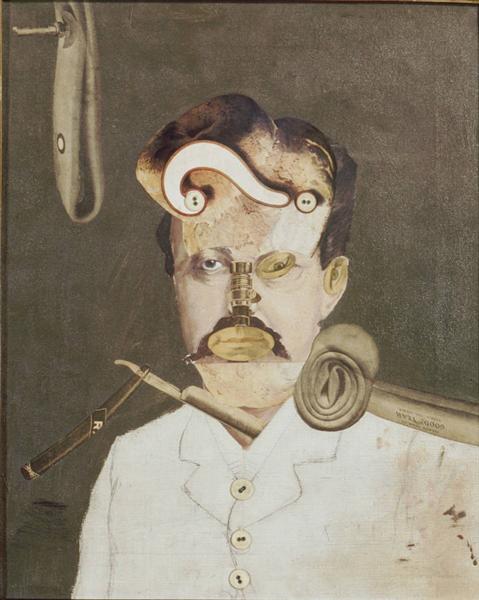

The images the couple have offered for public scrutiny have likewise been limited. They appear in photographs wearing sweaters or lab coats, not the business suits which might be deemed appropriate attire for a CEO and board member of BioNTech. This modest self-presentation carries considerable appeal in a time of excessive media stage-management and suggests a respected, traditional scientific ethos.

Because information about the two vaccine developers is so sparse, Uğur Şahin and Özlem Türeci can also serve as public objects of projection for matters reaching far beyond the COVID-19 pandemic. German chancellor Angela Merkel and federal president Frank-Walter Steinmeier have spoken, in the first-person plural, of Germany’s pride in the vaccine developers, while prime minister Armin Laschet claimed Şahin for North Rhine-Westphalia – where the immune engineer went to school – presenting him as a prime example of successful integration.

The vaccine represents a huge boost for the prestige of the Federal Republic as a country of science, a location for businesses and an open society. Much as in a bourgeois coming-of-age novel – this is what a vast majority of Germans would like to be.

But how open is German society? Was West Germany equally open back in the days when the two researchers were growing up there? How likely, historically and sociologically, were the careers of Şahin and Türeci? The biographies of the vaccine developers indirectly reveal much about the opportunities and, equally, the shortcomings of the ‘immigration society’ which arose with the recruitment of ‘guest workers’.

The latter term was misleading even in the 1960s, because it was clear even then that the guests were not about to go home. Three years after the signing of the German-Turkish recruitment agreement of 1961, employers’ associations saw to it that workers who had originally been employed on a temporary basis (initially they were 90% male) were not sent home, and that semi-skilled workers kept their jobs on a permanent basis.

This is exactly what happened to Şahin’s father, who came to work for the Ford Motor Company in Cologne and stayed on. He came from a remote area near the Syrian border and must have actively sought recruitment as a guest worker. His home region of Iskenderun, formerly the French administrated Sanjak of Alexandretta, was integrated into Turkey as late as 1939, a time when it had an Alevi population of 28%.

The Alevis are members of a religious minority related to Shia Islam, which places special emphasis on education and has produced many ambitious and successful people. Meanwhile, the Turkish government dismisses the Alevis and the Arab Alawites as misbelievers. Şahin has not confirmed whether his ancestors were Alevis, and has no time for personal interviews at present, for obvious reasons. But Turkish social media forums emphasize his Alevi heritage.

Another hint that this may be the case is the conspicuous silence of President Erdoğan, who normally likes to lay claim, through postings on social media, to successful foreign Turks – be they footballers like Mesut Özil or, most recently, the two Austrian-Turkish heroes of the Islamist terrorist attack in Vienna, Recep Tayyip Gültekin and Mikail Özen.

On photos circulating in Turkish social media forums, purporting to depict Şahin’s family, there is a picture in the background of Atatürk, the founder of the nation, whom the Erdoğan government denigrates as a drinker and womaniser. Şahin has denied the authenticity of the photos in an interview with a Turkish newspaper (he did not have time for an interview for Die Zeit, for which this article was originally written), but, if they are real, it would suggest that his parents were supporters of the secular republic, which embarked on educational programmes to overcome the country’s backwardness.

Türeci enjoyed conditions which were even more favourable for upward social mobility. She was born in Lower Saxony; her father was a surgeon and her mother a biologist. Both parents supported her as she attended high school and university – which is by no means a given for Turkish girls. Currently, only 4.5% of children of families from Turkish migrant background attend secondary school, and 19% of this group lack a school leaver’s certificate (for women the figure rises to 23%, indicating that they are at a further disadvantage in the family).

Türeci and Şahin are rare exceptions among the ‘population with origins in Turkey’ (the Federal Statistical Office uses this cumbersome term – türkeistämmige Bevölkerung – because not all people of this background are ethnic Turks). In the mid-1980s, Turkish candidates taking the Abitur school-leaving exam at any given secondary school could be counted on the fingers of one hand. The educational career of the two vaccine developers indirectly confirms the fact that, in Germany, the social origin of parents largely determines the course of their child’s education.

In 1984 Şahin graduated from the Erich-Kästner-Gymnasium in Cologne and was the first child of Turkish guest workers to do so. Simultaneously, the Federal Government under chancellor Helmut Kohl was running a campaign to persuade as many Turks as possible to remigrate. At the time, the discussion was still about ‘guest workers’ although, by then, many Turks had already been living in Germany for two decades raising half a million children under the age of 15 in Germany.

The recession which followed the second oil crisis hit former Turkish migrant workers particularly hard. Between 1979 and 1983, the number of unemployed rose almost fourfold due to industrial redundancies. The unemployment rate in the German-Turkish community grew to 16.7%, almost twice as high as among ethnic Germans. Nevertheless, only 12,000 Turkish families took advantage of the rewards of the ‘Return Promotion Programme’. The economic situation in their previous country was considerably worse, and Turkey was not interested in taking former guest workers back because, at the time, it was heavily dependent on their remittances.

Back then, remittances covered almost the entire trade deficit of Turkey, which was high due to the cost of energy and technology imports needed to modernize the country. Over the last twenty years, Erdoğan and the Turkish government have posed themselves as the patron saints of Turks living abroad, but in 1980 authorities made only cautious protests about issues such as the newly introduced visa requirement.

German Turks needed protection from discrimination, however. In the 1980s, a Turkish name meant that you were likely to secure a tenancy agreement only for a run-down house in a neglected neighbourhood. Furthermore, landlords were allowed to charge guest workers extra rent. This lasted until 1982, when the Stuttgart Higher Regional Court put a stop to the practice. Car insurance companies charged higher premiums because of a supposed higher accident risk, whereas German public sector workers could insure their cars at favourable civil service rates.

This discrimination also has a broader significance. It highlights the limits of the term and the debate about ‘structural racism’ that has spilt over from the United States to Europe over the past year. Certainly, the ‘white majority’ benefited from privileges in Germany, but it would be nonsensical, at least vis-à-vis Turks, to define minorities in the same racial terms as in the US. Moreover, one cannot impute anti-Turkish or racist attitudes to all German car owners paying the civil service insurance rate.

The crucial point is, however, that even the descendants of guest workers never benefited from positive discrimination or any affirmative action like in the US, for example through targeted language courses or further vocational training programmes. As education and labour market statistics show, there was and still is an acute need for support, especially for women with a migrant background.

Due to their generally low level of educational and vocational qualifications, Turkish migrants were the primary victims of structural changes introduced in the 1980s. After the German reunification, the situation deteriorated further. Due to mass immigration from East Germany, German Turks encountered new competition and by the end of the 1990s, their unemployment rate had risen to 24%.

Women were the most affected. While half of all women of Turkish origin were employed in 1985, the employment rate fell to 18.7% after the turn of the millennium. This promoted traditional models of family life, especially as almost two thirds of people from a Turkish migrant background continued to look for a partner in Turkey.

Over the past ten years, however, integration through marriage has been rising – in 2018, nine per cent of men of Turkish descent living in Germany, and six per cent of women married a German partner without a migration background. But these are recent developments.

Another factor that contributed to the minority’s isolation was far-right terror. In 1988, the first house to be inhabited predominantly by Turks in Schwandorf, Bavaria, burned down after an arson attack. Four people died. Attacks in Mölln and Solingen followed in the early 1990s. From that time on, many Turks lived in fear and retreated further into homes and neighbourhoods inhabited mainly by their compatriots.

The year 2000 saw the start of a series of xenophobic murders committed by the Nationalist Socialist Underground (NSU) which inspired considerable horror in retrospect, but no mass demonstrations on the scale of last year’s Black Lives Matter movement in the US.

It seems to be much easier for Germans (and other Europeans) to address racism in America than nationalism in one’s own homeland. After all, flag-waving and even violence is also practised by members of minority populations – as the riots of radical Erdoğan supporters against Kurds have shown in recent years.

To continue this series of inglorious German anniversaries, ten years ago the former Berlin senator of finance, Thilo Sarrazin, published a volume entitled Germany Abolishes Itself: How we are gambling with our country. The book was a compendium of nationalist and misogynistic prejudices. One could label the book also as openly racist, but that is off the point, it was an expression of traditional German xenophobia, and it categorized all German Turks collectively as Muslims.

At the end of the 1990s, the Federal Republic of Germany arrived at a hard-won consensus. A majority of the population and voters aspired to become an open-minded, cosmopolitan society. In 1999, the Red-Green government reformed the Citizenship Act and since then the path to integration has been easier, legally speaking.

Moreover, in spite of all obstacles, a German-Turkish middle and upper class has worked its way up. It now comprises more than a quarter of people of Turkish immigrant background, with an above-average household income in comparison with native Germans. Five per cent of this group are very wealthy, with more than 150% of the median German income. The billionaires obviously include Şahin and Türeci.

It is to be expected that socially mobile migrants in this category are likely to be sceptical of the minority or victim discourses pursued by the culturalist left. If the Christian Democratic Union of Germany (CDU) positions itself differently and more adroitly than in the 1990s, it has the potential to win many votes in this group. CDU leader, Armin Laschet, understood this at an early stage: he was one of the first German politicians to learn how to pronounce the muted soft g (ğ) in Uğur and the s-cedilla (ş) in Şahin.

However, there remains a large immigrant underclass whose children have not completed their schooling or gained a vocational qualification. They differ in their media consumption habits, and are likely to watch long hours of Turkish television while also using Turkish-language social media. Many are considerable fans of President Erdoğan, who is known to be anything but a supporter of an open, pluralistic society. This minority within the Turkish minority generally leads an isolated existence and is sceptical of the German state, despite the social benefits it offers. Hopefully, its members will be encouraged by recent news indicating how far children of migrant workers can go in Germany, even though these cases remain so exceptional.

This article was originally published in die Zeit in German on 6 January 2021.

This article is taken from the source: EUROZINE

published: 6. 3. 2021