Why was the German government and much of the German public so surprised by the invasion and Russian atrocities? Why did it take three months for the German public to understand the truth about this war? And why is it so difficult for Germans to talk about “fascist Russia”? Here are excerpts from an extensive text by an American historian published in Der Spiegel.

Germany is the most important democracy in Europe, perhaps even in the world. Germany is proud of its anti-fascism and its policy of memory. And the Germans are absolutely right that democracy requires a regular confrontation with history, especially the Second World War and the Holocaust. But it is not just German history, because almost all the German murders took place in territories that Germany did not come under its control until after 1938. Therefore, the politics of memory has always been intertwined with “Ostpolitik”, sometimes in a perverse way.

(…)

From a moral point of view, the mistake of the last thirty-five years has been to confuse categories such as guilt and responsibility, which lead in completely different psychological and political directions. Guilt is linked to power. If the Germans feel guilty for the Second World War and the crimes committed, then it is an invitation to others to emphasize and exploit this guilt. One can understand why Willy Brandt travelled to Moscow to achieve the establishment of diplomatic relations with the Eastern European states, especially the GDR. At that time, in the early 1970s, West Germany was just beginning to come to terms with its Nazi past.

However, viewing Brezhnev as an authority on German guilt was problematic from the start. Brezhnev had no interest in dealing with history. His troops had just invaded Czechoslovakia, 30 years after German troops had invaded. Under Brezhnev, the Soviet Union began organising military marches on 9 May, and the cult of war and victory was born. Brezhnev sought the Russification of Ukraine, and Kiev had no role to play in discussions about the German-Soviet past. And because the provisional alliance between the Nazis and the Soviets was taboo, Brezhnev also denied the existence of the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact (often called the Hitler-Stalin Pact), a German-Soviet non-aggression treaty concluded in August 1939, a week before the outbreak of World War II (…) The fate of Ukraine was important neither to the Germans nor to the Soviets. Ukraine was invisible.

(…)

The unspoken condition of “Ostpolitik” was not to talk about Ukraine, which was in fact the central theme of the politics of memory. In the 1930s and 1940s, the country suffered from a double colonisation by Moscow and Berlin. The rapprochement between Moscow and Bonn in the 1970s and 1980s reinforced the silence on this issue.

(…)

In the 19th century, the Ukrainian national movement was one of many national movements in Europe. At the end of the First World War, Ukrainians, like other peoples living in disintegrating empires, tried to create their own state. The Ukrainian People’s Republic was caught between two fronts: the Germans recognised it but wanted to exploit its food resources, and the Bolsheviks wanted to destroy Ukraine. Ukraine was a nation, which is why Lenin and his comrades founded the Soviet Union as a union of union republics with national names. This eventually allowed Stalin to sort of internally colonize Ukraine and other agricultural areas of the USSR. When the collectivization of agriculture proved ineffective, he blamed the Ukrainians and instituted a series of measures against the Ukrainian Republic of the USSR that resulted in the starvation of some four million people. Hitler saw this as a pattern. He, too, believed that the black land in Ukraine could become a profitable colonial project. Ukraine was to be the environment that would enable Germany to become a world power.

(…)

In the 1980s, a dispute among German historians (Historikerstreit) revealed a fundamental problem in German memory politics. German historians used German sources to talk to Germans about other Germans. The most important rule of postcolonial memory politics, however, is to listen to the voices of the colonized. (…) But this meant speaking Yiddish, Polish, Russian, Ukrainian, Czech, Hungarian and other languages, which West German historians avoided. In the late 1980s, such a perspective was completely absent. When the Soviet Union disappeared, few in West Germany thought about Germany’s colonial past in Ukraine. And almost no one thought that Germans should listen to Ukrainian voices to understand part of their past. In this sense, the German colonial tradition continued.

(…)

Trading with Moscow autocrats was morally justified by the Second World War. Ukrainians were seen as troublemakers who got in the way of this narrative. This was convenient because it meant that there was no need to morally question trading with Russia. If Ukrainians speak Russian, why couldn’t they be Russian? If they speak Ukrainian, they are nationalists who have not learned the lessons of World War II. It was nothing but a subtle form of colonial arrogance.

(…)

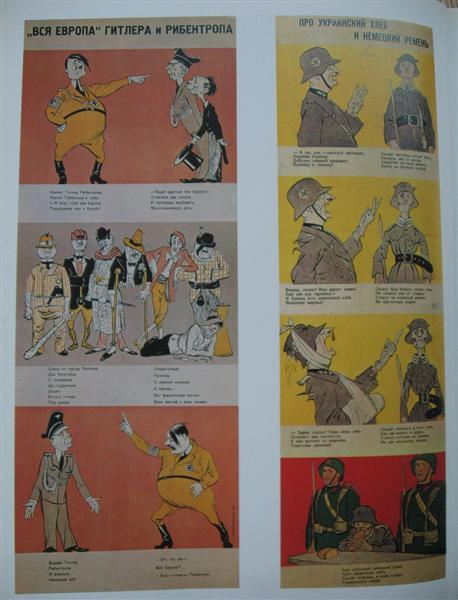

The confusion of responsibility and guilt has become a Russian weapon in this decade. On the domestic scene, Putin has moved the Brezhnev cult of the past in a clearly fascist direction: towards the cult of victory, the cult of the leader, the cult of death. For Putin, a “Nazi” today is anyone who has invaded Russia, or anyone who the Russian leadership believes might invade Russia, or anyone who opposes Russia in any way. Serious involvement in Nazi ideology has and rarely does occur. From such a perspective, it is impossible to consider oneself a fascist. So the fascist is by definition the latter, and the Russian is by definition anti-fascist – even if what he does is obviously fascist. That is why the history of Russian collaboration with the Nazis is not mentioned at all in Russia today. Laws forbid debates on the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, and the difficult subject of Stalin’s crimes, including the famine in Ukraine, is officially taboo.

(…)

Russian memory policy is thus the exact opposite of German memory policy – and yet this has never been a problem for Germany. Because the relevant category was guilt, not responsibility, the Germans did not ask how Russia was actually dealing with its past. Assigning blame, as Vladimir Putin knows, is a tool to exert domination. Putin and his comrades-in-arms love to use German guilt as a political resource. (…) The Russians like to boast about this strategy when there are no Germans in the room. The tragedy of recent years, however, is that the Germans have sought atonement for their fascism from people who are themselves clearly fascists.

(…)

If German politicians had been aware of the significance of the Ribbentrop-Molotov Pact, they would hardly have morally justified the purchase of natural gas from Russia. Instead, German payments for fossil energy helped finance two more Russian wars of aggression in Eastern Europe. After the second invasion, the Germans claimed that their dependence on Russian oil and gas limited their political options. But this dependence was a conscious political decision; there were other options. Since then, this dependence has shaped the German debate, which in turn confirms the shortcomings of Eastern politics and the culture of memory. Gerhard Schröder is merely a vulgar symbol of a general phenomenon.

(…)

The Germans are right: democracy can only flourish in constant confrontation with history. The catch is that history is always unpleasant, because the voices that hurt must be heard. The Germans should have started the debate on Ukraine 30 years ago, now it has happened in just three months. In a moment of such cacophony, it is inevitable that one will sometimes revert to old colonial habits or consider oneself a victim.

Progress in German debate and politics is, of course, encouraging, but Germany must come to terms with its history, especially now, in these weeks and months that will also go down in history. Germany has a chance to break with its colonial tradition and finally take the right side in the war against fascism. German democracy needs this, and the rest of us (not just Ukrainians) need German democracy.

The full length essay appeared in Der Spiegel on May 27, 2022.

This article was translated from the Czech version published at časopis Přítomnost.

published: 13. 6. 2022