Pablo Picasso, the iconic “Artist of the 20th Century,” died fifty years ago. A major exhibition commemorating his work begins at the Albertina in Vienna on Friday 17 March. We present a personal Picasso reflection by the well-known Czech visual artist Jiří David.

The date is 8 April 1973. Soon, in the summer, I will be seventeen. A year from now, I will graduate from the mechanical engineering school in Ostrava-Vítkovice and I will have this terrible desire to become an artist. Yes, an artist, the one I read about with bated breath in the books my grandfather used to bind at the end of the world, in the small village of Dolní Poustevna near the German border. My childhood…

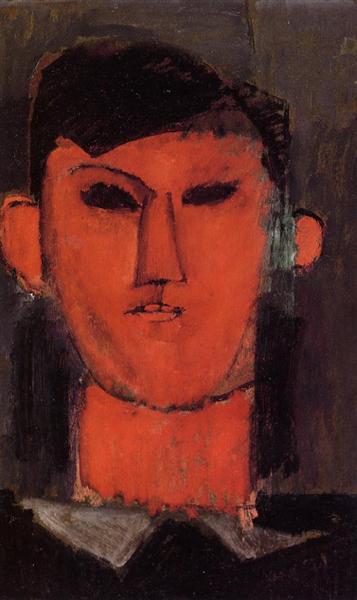

Vincent van Gogh, Paul Gauguin, Paul Cézanne, the magic of their lives, the power of their paintings, even if only in imperfect reproductions. And then a blow to the neck – Pablo Ruiz Picasso. There was no getting around it, he oozed incredible energy, in every period, whether in existential melancholic blue or Harlequin pink. And then African and on and on and on. But there’s no point in cramming yourself into an art historical role, no point in repeating what has been interpreted a thousand times forever. Yes, analytical, synthetic cubism, inspirational buddy Georges Braque, Bateau-Lavoir – Paris.

Yes, I was 17 years old when Pablo Picasso, then ninety-two, died on April 8, 1973. No, he wasn’t my idol, I guess I was more envious of his wonderfully free, uncommitted life, all those beautiful women, the sun of his late houses, studios. And yet there are suggestive glimpses, probably from documentaries of his life, where his images absorb me and still surprise me, even if they are notorious and often much-maligned experiences. For after all, every man in the street around the world has long known that any illegible painting that cannot be grasped with illusory ease is a cunning à la PICASSO. Hey, Picasso (!)… and ridicule is guaranteed. The name has thus forever overtaken the knowledge of his art and become an emblem tattooed in the memory of universal humanity. Rightly and wrongly. Rightly so, for his incredible artistic vitality, a creativity that until then was literally unseen, unprecedented. Had it not been for his groundbreaking artistic transformations, we might still be stuck in many stereotypes today. The unfair ridicule of uptight petty bourgeoisie (the model scheme) and in the forms of not only thousands of disgraced artists who denounced Picasso’s work in a haze of jealousy for decades, in fact to this day. As well as the recent totalitarian regimes, when Picasso’s work became synonymous with so-called “entartete Kunst” or degenerate art.

I must thus necessarily go back even in my own lifetime to try to find the neuralgic points that (un)bind me to his work. For it has taken many decades since my adolescence before I have been able to see his famous paintings other than those that, fortunately, thanks to the unusual providence of Vincenzo Kramar, are owned by the National Gallery in Prague. I stood in silent humility in the 1990s, for example, in front of his celebrated Guernica at the Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía in Madrid, and most recently four years ago at The Museum of Modern Art in New York for his equally world-breaking 1907 painting Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (The Avignon Ladies), which now seems to be just a conventional, innocuous, pleasantly aesthetic painting, almost a pleasant souvenir. And so, in this context, it is actually really incomprehensible (but perhaps more or less telling) that this groundbreaking twentieth-century painting did not come into common knowledge until decades after its creation. More specifically, after more than thirty years. By the way, where are similarly groundbreaking stigmatic works hidden on the body of contemporary art today? Do they exist in the flurry of dozens of instant quasi-works, where they are born in the morning but are no longer known in the evening? Do they exist in dozens of ideological constructions or in the dishonoring of the power of the individual artist’s uniqueness by a kind of collective meeting, a toxic sludge of untalented or self-appointed cultural officials? When does art lose its personal dimension and become part of an administrative machine? When does art transform into a noiseless anonymous foam ready for trendy political and social constructions?

Fortunately, even in art, unconventionality is usually not directly proportional to any kind of independence, and independence is usually not a condition for unconventional authenticity. In other words: as I am gradually learning on my own with age and perhaps experience, which can never be eclectically acquired or theoretically and priory ordered, Picasso unconsciously initiated me into the futility of art. Art as a faculty of form that refracts a language that has already become its own content, but without losing its meaning. Art as the sum of intuitions in a moment of sustainable intelligibility. Art as discovery, not construction, for if something is incomprehensible, it does not make it any less real. In other words: meaning is not a construction, but a discovery. A form that takes into account, builds upon, transforms, inverts and emphasizes. It can be both figurative with the full responsibility it demands, but it can also be non-figurative with the same intensity, as well as non-material when reason is relevant. A work of art is defined by the art world and the art world by works of art. Nothing can be invented. What you don’t invent doesn’t belong to you. No reasoning and no theory can replace sight. Knowledge can only multiply the power of the exploratory eye, but it is no substitute for active experience. Our knowledge is sensory. Which is still the only “medicine” in art, in the polymorbid fields of necessary inner uncertainties, vanities and doubts.

It’s half a century years after the death of genius, when the very word genius is already understood as something inappropriate, suspect, and the questioning of history confirms the triumph of the entertainment industry not only on social media, but also within culture and art itself, in galleries, institutions, museums. Picasso’s legacy thus actually carries, in the time we are living, a defiance of this administrative power, of dullness and malice. Something like “don’t tell me what you know, tell me what you don’t know”. “Don’t show me what you can do, show me what you can’t do.” “I don’t care what you can do, I care what you can’t do.”

The art of not knowing is the supreme art, the art of not knowing is impotence, where the meaning of art is born in the conflict between the vision of the artist and the vision of the recipient. When authenticity in art is equal to the conscience of the individual artist and is not just a game of witnessing. When the power of the artist lies not in the identification with the subject, but in the freedom with which he treats the subject.

This article was translated from the original published at Přítomnost.

published: 20. 3. 2023