To conserve is to preserve the status quo and resist change; revolutionary is to desire change, usually by violent means. Suppose that a certain country had a most agreeable constitution and liberty, but that this liberty was not to the liking of certain men who liked to oppress their fellow-men and to take undeserved advantage of them, and that these men determined to abolish the constitution and to introduce despotism through conspiracy. All the friends of liberty in this country will certainly wish to preserve their good constitution; they will therefore be conservative, but all absolutists will be revolutionary. (Karel Havlíček)

The now-classical conservatism of the 18th and 19th centuries, seeking to preserve feudalism and Christianity, gradually took on democratic and left-wing values during the 20th century; it was forced to do so especially in the 1960s. In response to this trend, right-wing neoconservatism emerged in the United States. Similarly, European neoconservatism developed, especially in England, and after 1989 in some post-communist countries. While it shares a right-wing orientation with neoliberalism, it differs from it in many ways.

The legitimacy of right-wing preservation of everything old or ancient depends on whether and to what extent it can be beneficial. Neoconservatism seeks to preserve political traditions, established principles, customs, morality, religion, private property, family and patriotism. It opposes egalitarianism and rapid change. It has not got rid of its roots in the distant past, which are now outdated. The right, in order to win over the rank and file, must necessarily lie to and manipulate them (which is not to say that the left does not lie to and manipulate them as well, though it does not necessarily have to).

The disadvantage of conservatism over democracy and left-liberalism is that it relies less on facts and sober reason. Its theorists, e.g. Günter Rohmoser and Ernst Topitsch, have explained this by saying that every ideology has its ever-present and pervasive strengths and weaknesses, and yet has or can or may have an influence on the formation of societies.

Neoconservatism is based primarily on the shortcomings of democracy and liberalism. In contrast, it hinders social development and perpetuates untenable old myths, thereby suppressing critical realist thinking in individuals and societies. Myths are dangerous, among other things, because they have the capacity to infect other spheres of human feeling and thought, and thus hinder the judgment and civilisational development of humanity. In the USA, for example, not a few people still think that the Earth is flat, and these same people are prone to believe other right-wing myths.

The Czech educator and social philosopher Pavel Mühlpachr described the main features of today’s “Hayekian” and conservative right-wing world: “The market mechanism and competition have become universal economic principles… In the society of the global economy, the emphasis is increasingly on individual performance; therefore, contemporary society is also characterized as a performance society or meritocratic society. Implicit in the principle of meritocracy[1] is also the assumption of social inequality… Individualism, rooted in the ancient inspiration of the Renaissance, is now growing to monstrous forms… Social and economic dynamism leads to a constant acceleration of development and pushes the individual to ever greater dynamism… Man cannot keep up with it; it becomes a source of ever greater stresses for him…. Money has always been one of the main measures of value. Recently, however, it has become the universal, even the only measure – everything, all values are being converted into money… The pressure of economics then leads to a one-sided narrowing of human interests and human activities into economic interests and activities, the elevation of money to the main, if not the only, goal. And thus to a fundamental deformation of man.”[2]

Neoconservatism has long been invoked as a conjunctural political and socio-cultural phenomenon whose causes lie in the crisis of modern society, without, however, offering unifying new values. Like Christianity, it is merely a faith that uses the same methods to defend itself.

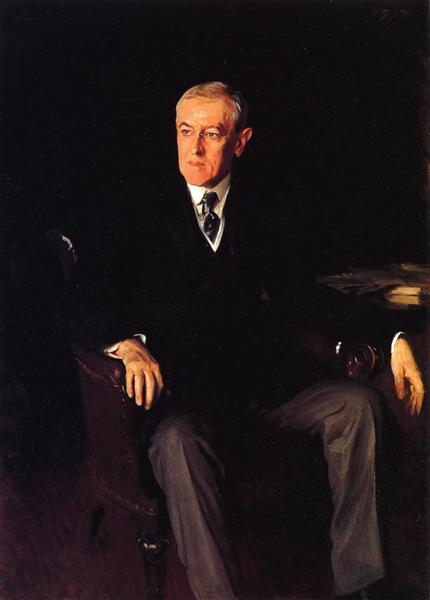

It is telling how the content of the concept of the New World Order has changed over the course of the 20th century. It was first used by the American President Woodrow Wilson, a modernist, democrat and humanist, when he promoted the idea of a League of Nations to ensure understanding and peace between nations. However, the League of Nations, the post-1945 United Nations, never achieved the significance envisaged by its founders, as it clashed with reactionary and, after 1970, post-modernist and neoliberal forces that, under the guise of freedom, opened up a space of power for autocrats who manipulated and programmatically disempowered ordinary people.

Potential and actual autocrats used increasingly sophisticated demagogic and even lying propaganda. Their vehicles were and still are the most financially powerful groups and people whose primary interest is unbridled power, and whom the American writer Kurt Vonnegut described as psychopaths. It can rightly be argued that it was people of a similar type who caused the First and Second World Wars, who benefited from the Cold War and who pursued policies that are increasingly less defensible in both substance and morality.

All this is, among other things, further proof that flawed, truth-based theories, ideologies and theses necessarily have flawed consequences. Critics of the New World Order have long pointed out that a tiny handful of transnational financial elites are manipulating humanity, that they are trying to establish a closed society led by a single, elusive power that keeps the public ignorant by by controlling the mainstream media, by flooding the public with numerous unsubstantiated, irrelevant and contradictory information alongside substantiated data, by promoting material consumption, contentless entertainment, workaholism and relativising morality. The result is, among other things, the steady deterioration of virtually all indicators of the culture of thought of the majority of the population and its general, not only mental, degeneration.

It can be argued that the power elite can also mean the ideological elite, i.e. that among the most powerful people there are also people who are judicial and widely educated, i.e. those who “know”; however, the development of the world in recent decades refutes this objection. The world continues to become more polarised, threatened by climate change and overpopulation, but the ‘elite’ do little or nothing about it. Recently, it has been moving away from mindless economism and towards environmentalism, but this is not enough.

One cannot help but wonder who is actually supposed to rule the world. Is it to be the unjudgmental and ignorant people or the (un)judging and (un)knowing powerful? Democracy is proving naive and suffering from crises, but even more naive are the current pseudo-democracies and autocracies, for they have no hope of lasting success.

Neither the Socratic recovery of society from below nor the Platonic “there will be no end of woes until philosophers become kings or kings become philosophers” has taken hold. The only solution is a psychologically based and broad-based education of society, which alone can produce enough judgmental and morally integrated individuals and groups.

There was, is and will be nothing better than democracy or Popper’s open society. The education and rehabilitation of society is an extremely laborious and lengthy path, but it is the only possible path. Democracy backed by morality, sufficiently oriented people, ethically focused sciences, arts and humane macroeconomics is, however, still a mere “dream”.

From the forthcoming book The Twilight and Dawn of Democracy.

[1] A government of the important, the best

[2] Pavel Mühlpachr, Sociopathology, Masaryk University 2009

This article was translated from the Czech original translated in the online revue Přítomnost.

published: 27. 3. 2023